src: click

Sag uns ja nicht die Wahrheit, wir haben dich gewarnt!

src: click

Sag uns ja nicht die Wahrheit, wir haben dich gewarnt!

- who translated the entire Ukrainska Pravda article into chinese. 🙂

So now we can use Qwen 3.5. 🙂

edit: The english translation is basically flawless in terms of legibility and integrity of concepts so use that one.

Short comment if I may - I have always seen ukraines “oh our MPs find it so hard to find the motivation to vote”, and “oh 20 randoms vanish before every vote, we have mounted an investigation into whats causing that” simply as Ukrainian stalling tactics to be able to prolong the war.

Selenskyjs new arguments on the international stage of “what might be able to get a vote and what not” scream manipulation of the negotiation narratives and goals, more than anything else.

And they arent even good at it. With that - I present you with the full machine translation on the Ukrainska Pravda article, mentioned in the previous posting.

Analysis of Ukrainian Political Crisis & Parliamentary Collapse

Eine Recherche der Ukrainska Pravda

Laut Ukrainska Pravda: Untersuchung enthüllt, wie „Umschlag-Politik”-Verfolgung zum Zusammenbruch von Selenskyjs parlamentarischer Kontrolle führte

Eine Untersuchung von Ukrainska Pravda enthüllt, wie der Einschüchterungseffekt, der durch die Ermittlungen zur „Umschlag-Politik” (Bestechungsgelder in Cash für Stimmen) ausgelöst wurde, zum Zusammenbruch der Kontrolle der Fraktion von Präsident Selenskyj über das Parlament geführt hat. Die Analyse weist darauf hin, dass die strukturelle Spannung zwischen Antikorruptionsmechanismen und legislativer Effizienz die Ukraine vor eine doppelte Krise stellt: Stagnation bei den IWF-Reformen und eine fiskale Klippe. Dies spiegelt tiefe institutionelle Dilemmata innerhalb der Kriegs- und Nachkriegsregierungssysteme wider.

![Bild]

Die Ukraine hat gerade den härtesten Winter ihrer Geschichte überstanden und sollte sich im frühen Frühling eigentlich erholen können. Doch leider ist das unwahrscheinlich. Seit dem Ausbruch des umfassenden Krieges war die Gefahr eines wirtschaftlichen Zusammenbruchs noch nie so unmittelbar.

Das Land betritt seinen schwierigsten Frühling mit einer unausgewogenen Wirtschaft und einem Zustand, der fast vollständig von der Rechtzeitigkeit externer Kredite abhängt. Im wörtlichen Sinne hängt die Fähigkeit, erfolgreich weiterzukämpfen, davon ab, ob die Behörden die wirtschaftliche Kontrollierbarkeit und finanzielle Stabilität aufrechterhalten können.

Daher muss die Arbeit der politischen Führung der Ukraine dem Ziel untergeordnet sein, Finanzierungsquellen für den Staat zu finden.

Erstens geht es darum, den von der EU bereitgestellten Kredit über 90 Milliarden Euro freizugeben.

Zweitens müssen die Bedingungen für die IWF-Hilfe und das Programm „Ukraine-Fazilität” schnell erfüllt werden.

Die erste Aufgabe ist äußerst schwierig, weil Kiew nur begrenzten Einfluss auf Ungarn hat, das tief in Wahlpolitik und Ukraine-Feindlichkeit verstrickt ist. In der Zwischenzeit hätten die „Hausaufgaben” im Zusammenhang mit der Reformagenda ohne Verzögerung umgesetzt werden sollen.Aber wie man so sagt, gibt es ein Problem—das einzige Gremium, das in der Lage ist, die notwendigen legislativen Reformen zu verabschieden, die Werchowna Rada, bröckelt vor aller Augen.

„Am 5. März hielt Präsident Selenskyj ein großes gemeinsames Treffen mit der Regierung, dem Präsidialamt und dem Parlament ab. Nach dem Treffen führte die Rada-Führung ein mehrstündiges Gespräch mit Kachka (Vizepremiersminister für europäische Integration). Der Vizepremiersminister schlug vor: ‘Ich habe eine grandiose Konzeption—300 Gesetzentwürfe zur europäischen Integration beim Parlament einreichen.’ Stefanchuk antwortete: ‘Taras, vergiss es. Du hast den ersten Cluster (der EU-Beitrittsverhandlungen)—reiche sogar nur einen (!) Gesetzentwurf ein, und lass uns versuchen, ihn durchzubringen. Warum diese ‘Maschine’ 300 Mal im Leerlauf laufen lassen?’ ” — berichtete ein Augenzeuge des Dialogs der Beamten.

Tatsächlich beschreibt dieser Kontrast zwischen dem massiven Umfang dringender Probleme und der tatsächlichen Fähigkeit des Präsidialteams, Beschlüsse durch das Parlament zu bringen, präzise die Katastrophensituation, auf die die Behörden zusteuern. Das gesamte Land gerät folglich in eine Krise.

Alles begann mit dem rücksichtslosen Angriff auf die Antikorruptionsbehörden im Juli letzten Jahres, bei dem die Werchowna Rada die Rolle des Vollstreckers zugewiesen bekam.

Nach dem „Mendych-Skandal”, der Aufdeckung zahlreicher Korruptionsfälle innerhalb des Präsidialamts und der Regierung sowie dem Verdachtsschleier über „Umschlag-Anreize” für Abgeordnete, ist die einst mächtige monopolistische Mehrheit auf eine prekäre Größe geschrumpft.

Darüber hinaus verlor die Partei Diener des Volkes nach dem Start einer „umschlagartigen politischen Verfolgungs”-Operation des Nationalen Antikorruptionsbüros (NABU) gegen Julija Timoschenko auch die Möglichkeit, nach „externen Verbündeten” zu streben.

Systematisch darauf ausgerichtet, die „Mehrheit zu zertrümmern”: Vorwürfe, Timoschenko „kaufe Herzen”

Das Ergebnis ist, dass sensible Gesetzentwürfe, die für die IWF-Zusammenarbeit entscheidend sind, bei Abstimmungen wiederholt scheitern. Selbst mit aller Kraft kann die Partei Diener des Volkes kaum 120 Stimmen zusammenkratzen, weit entfernt von den erforderlichen 226 Stimmen.Warum ist die Partei von Präsident Selenskyj in einen Zustand der (Semi-)Desintegration geraten? Hat sie noch die Fähigkeit, die Kräfte der Abgeordneten neu zu sammeln? Können Timoschenko und andere „Oppositions”-Figuren auf einen konstruktiven Kurs zurückkehren? Noch wichtiger: Kann das Land ohne externe Hilfe einen wirtschaftlichen Zusammenbruch vermeiden?

Der fehlende Kern oder das Dilemma der „nicht länger Mehrheit”

Die sogenannte „einzelne Mehrheit” hält tatsächlich keine Mehrheitssitze mehr. In den frühen Phasen der Invasion vereinigten sich die Abgeordneten, und das Parlament funktionierte mit voller Kapazität. Doch als dieser große Krieg Jahr für Jahr andauerte, verschlechterte sich die Situation allmählich.Einige gewählte Vertreter sind im „Uschhorod-Kessel” (ein Slangbegriff, der Unordnung impliziert) verstreut, einige sind ins Ausland geflohen, und andere wurden aus den Fraktionen ausgeschlossen.

Instabilität innerhalb der Partei Diener des Volkes hat es immer gegeben. Trotzdem behielt die Fraktion immer eine stabile Kernkraft bei. Vor dem Krieg und während des „Mendych”-Vorfalls blieb ihre Kernmitgliederzahl bei etwa 170 bis 180.

Darüber hinaus konnte die Partei Diener des Volkes auch die Oligarchen-Gruppe „Vertrauen” von Andriy Verevsky hinzuziehen, die immer bereit war, etwa 20 loyale Stimmen bereitzustellen. Es gab auch die Möglichkeit, eine Vereinbarung mit der Gruppe „Für die Zukunft” unter der Leitung von Ihor Palitsa zu treffen. Obwohl ihre Abstimmungsdisziplin schlecht war, konnten sie bei Bedarf immer noch 10 bis 15 Stimmen sammeln.

Plus jene Stimmen, die von den Abgeordneten selbst als „Gefangenen-Stimmen” bezeichnet werden, die aus den Oligarchen-Lagern von Serhiy Lyovochkin und Dmytro Firtash sowie der (Rest-)Gruppe der Partei „Oppositionsplattform – Für das Leben” unter der Leitung von Vadym Stolar stammen.

Die Fraktion von Julija Timoschenko suchte ebenfalls immer nach Möglichkeiten, Einfluss auszuüben. Sie handelten mit Stimmrechten—manchmal für zusätzliche Redezeit, manchmal für Sendezeit im Programm „Vereinigtes Marathon”, und manchmal, um von den Strafverfolgungsbehörden zu verlangen, Ermittlungen gegen ihre Mitglieder einzustellen.

Kurz gesagt, trotz 180 Sitzen war die Partei Diener des Volkes immer in der Lage, gemäß der vom Präsidialamt ausgegebenen Agenda abzustimmen. Bis zum Sommer 2025, als sich die Situation stark zum Schlechteren wandte. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt versuchte das Präsidialamt, eine kleine Antikorruptionsrevolution in der Ukraine zu starten, erlitt jedoch letztendlich eine katastrophale Niederlage beim „Papp-Maidan”-Vorfall.

In diesem Krieg zwischen dem Präsidialamt und den Antikorruptionsbehörden diente die Werchowna Rada lediglich als Vollstrecker des „kriminellen Plans”. Doch obwohl der Präsident nach diesem Skandal seine Unterstützungsrate erfolgreich wiederherstellte, erholte sich das Parlament nie von dem Schlag.

Als NABU die „Umschlag-Anreize” in Frage stellte, insbesondere bei Zielpersonen, die Juriy Kisyel, einem Abgeordneten der Partei „Batkiwschtschyna” (Vaterland), nahestanden, begann die bereits fragile Struktur der „einzelnen Mehrheit” noch heftiger zu wanken.

Die Partei Diener des Volkes beschwert sich jetzt, dass in den Anschuldigungen gegen Kisyel und anderes beteiligtes Personal erwähnt wird, sie hätten Zahlungen erhalten für die Abstimmung zur Genehmigung „bedeutungsloser Fälle zur Ratifizierung zwischenstaatlicher Abkommen”.

„Während des gesamten Krieges hat die Werchowna Rada nur zwei Abstimmungen durchgeführt, die ‘vestierte Interessen’ betrafen: die Sojabohnen-Änderung und der Fall zur Beschaffung von Ausrüstung für das Kernkraftwerk Chmelnyzkyj. Das war’s. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt griff das Nationale Antikorruptionsbüro plötzlich ein und behauptete, Abgeordnete hätten Bestechungsgelder für die Genehmigung internationaler Abkommen erhalten. Das ist völliger Unsinn. Jeder versteht, dass Abgeordnete unter Druck stehen wegen des Krieges zwischen dem Präsidenten und den Antikorruptionsbehörden. Okay, lass sie zuerst interne Widersprüche lösen, dann werden wir abstimmen.” — erklärte ein einflussreicher Abgeordneter der Partei Diener des Volkes bezüglich der Empörung der Fraktion.

Die Abgeordneten wichen schüchtern der Tatsache aus, dass der Fall zur Ratifizierung internationaler Abkommen nur einer der Abstimmungspunkte war, bei denen bestochene Abgeordnete „Umschlag-Anreize” erhielten. Aber der Schlüssel ist, dass es innerhalb der Regierungsfraktion tatsächlich einen allgemeinen Konsens bezüglich der oben genannten Interpretation der Maßnahmen der Antikorruptionsbehörde gibt.

Seit der Gehaltserhöhung für Abgeordnete im Dezember letzten Jahres ist die Nachfrage nach Bargeldzuschüssen in Umschlägen natürlich verschwunden. Jetzt, wie parlamentarische Quellen Ukrainska Pravda versicherten, besticht niemand mehr Abgeordnete der Partei Diener des Volkes. Aber sie nehmen auch nicht mehr an Abstimmungen teil.

„Wir haben ein hervorragendes Nationales Antikorruptionsbüro und eine spezielle Antikorruptionsstaatsanwaltschaft—sie sind Helden. Was das betrifft, dass wir jetzt keine Gesetze bezüglich Fondsmechanismen oder des IWF verabschieden können—das sind trivial Details. Das interessiert niemanden.” — bemerkte sarkastisch ein Abgeordneter aus der Führung der Partei Diener des Volkes.

„Viele Leute sagen: ‘Ich stimme lieber für nichts, als dass das Nationale Antikorruptionsbüro anklopft.’ Die Kernmitglieder der parlamentarischen Fraktion sind auf 110-120 gesunken. Wie man über komplexe Gesetzentwürfe abstimmt—es gibt einfach keine Lösung. Schließlich kommen die NABU-Leute nicht, um für uns zu stimmen.” — ergänzte ein Kollege Abgeordneter müde und zog es vor, die ganze Schuld auf diejenigen zu schieben, die die „Umschläge” aufdeckten, anstatt auf diejenigen, die sie füllten.

Die Abstimmungen im Parlament am 10. März scheinen nur das zu bestätigen, was Ukrainska Pravda-Quellen sagten. Die Abgeordneten sollten über den sensiblen Gesetzentwurf zur sogenannten Digitalplattform-Steuer und mehrere Regierungsentwürfe abstimmen.

Doch obwohl der Gesetzentwurf zur Digitalplattform-Steuer nur eine Erstlesungs-Abstimmung erforderte, konnte er dennoch nicht verabschiedet werden. Dabei waren umstrittene Klauseln zur Besteuerung internationaler Pakete unter 150 Euro und zur Erhebung der Mehrwertsteuer auf Einzelunternehmer ursprünglich geplant, vor der zweiten Lesung in den Gesetzentwurf aufgenommen zu werden.

Selbst unter diesen gelockerten Bedingungen konnten der Gesetzentwurf und die Regierungssozialprojekte der Partei Diener des Volkes nur 120-130 Stimmen Unterstützung gewinnen.

Bei der Abstimmung am 10. März muss man jedoch nicht nur auf die gescheiterten Gesetzentwürfe schauen, sondern auch jene prüfen, die Unterstützung erhielten. Andernfalls kann kein vollständiges Bild erhalten werden.

Die ersten zwei Abstimmungen (Genehmigung des Übereinkommens zur Bekämpfung der Bestechung ausländischer öffentlicher Bediensteter im internationalen Geschäftsverkehr und Ermächtigung der Hauptnachrichtendirektion des Verteidigungsministeriums, spezielle Funkfrequenzen zu nutzen) erhielten breite Unterstützung im Parlamentssaal und wurden reibungslos verabschiedet. Die Partei Diener des Volkes gab jeweils 183 und 170 Stimmen dafür ab. Aber nur 6 Minuten später, während der Abstimmung zum „Fall Digitalplattform-Steuer”, verschwand dieses Unterstützungspotenzial mysteriöserweise.

„Niemand versteht, wie das sein kann: Wir müssen von jedem Paket Geld einsammeln, die Bösewichte sein, während Julija und der Präsident ihre neue Runde von Tausenden Griwna, eSupport usw. verteilen wollen. Jetzt müssen wir die Schuld für sie übernehmen, wird der Präsident danach unterschreiben? Wir haben das schon erlebt, dass er sich direkt die Hände wäscht und nicht unterschreibt.” — erklärte ein Abgeordneter der Partei Diener des Volkes, der an der Behinderung des IWF-Gesetzentwurfs beteiligt war.

„Die Führung denkt, er kann weiterhin willkürlich Ideen ausgeben, und wir werden ohne Widerspruch dafür stimmen. Da wir zum selben Team gehören, teilen Sie bitte die öffentliche Verantwortung mit uns. Selbst nur eine Kommunikation mit den Abgeordneten wäre gut. Aber für uns ist es einfacher, bestimmten Leuten routinemäßige Vorteile zu streichen, hart zu kämpfen, um erbärmliche 1 Milliarde Griwna für Wohnungen für Binnenvertriebene zu beschaffen. Und dann können wir lässig 10 Milliarden Fonds für einige absurde Projekte bereitstellen—wie einen Gesundheitscheckup-Plan für Menschen über 40—nur weil diese in abendlichen Fernsehansprachen glamourös klingen.” — ergänzte eine Ukrainska Pravda-Quelle wütend bezüglich der internen Situation der Partei Diener des Volkes.

Die Präsidentschaftsfraktion beklagt ein weiteres Problem—es wird „zielgerichtete Arbeit” gegen Diener des Volkes geleistet.

„Vor jeder wichtigen Abstimmung verschwinden plötzlich 15-20 unserer Abgeordneten. Sie waren ursprünglich anwesend—dann plötzlich verschwunden. Diese Leute gehören keiner festen Gruppe oder organisierten Fraktion an, nur einige unverbundene zufällige Personen. Wir untersuchen den Mastermind dahinter, weil diese Situation sehr verdächtig erscheint,” — enthüllte eine Führungspersönlichkeit der Partei Diener des Volkes.

Interne Quellen der Partei Diener des Volkes sagten, sie vermuteten, dies sei eine Aktion von Poroschenko oder Timoschenko, um die Regierungskoalition zu zerlegen. Insbesondere da Timoschenko selbst in der Vergangenheit von NABU für ähnliches Verhalten aufgezeichnet worden war.

Allerdings sind die Gesprächspartner von Ukrainska Pravda in der Parlamentsführung und den Fraktionen nicht allzu klar darüber, was diejenigen, die versuchen, die Partei Diener des Volkes zu spalten, eigentlich wollen.

„Weder die Verfassung noch das Gesetz führen das Fehlen einer Koalition als Grund für den Rücktritt der Regierung oder eine andere Beendigung ihrer Befugnisse an. Dies ist auch kein Grund für eine vorzeitige Auflösung des Parlaments. Erstens ist es nicht mehr möglich, über eine vorzeitige Auflösung des Parlaments zu sprechen, da das Parlament bereits Überstunden macht. Zweitens kann das Parlament während des Kriegsrechts einfach nicht aufgelöst werden. Also werden sowohl die Regierung als auch das Parlament handeln. Es ist vergebliche Mühe,” sagte eine Führungspersönlichkeit der Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’, während sie hilflos die Hände ausbreitete.

Wie das Parlament ohne Motivation und ohne „Süßigkeiten” überlebt

„Das Parlament arbeitet seit fast 7 Jahren. Ich sage nicht, dass es schwierig und ermüdend ist. Aber nach so langer Zeit würden selbst Gurken im Fass fermentieren und sauer werden,” beschwerte sich ein hochrangiger Beamter der Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’.Eine parlamentarische Quelle von Ukrainska Pravda gab zu, dass die 9. Einberufung ihr Potenzial erschöpft hat. Heutzutage kann schon der kleinste Instabilitätsfaktor zum internen Zusammenbruch führen.

So hat das Parlament kürzlich den Vorsitzenden des Wirtschaftsausschusses, Dmytro Natalukha, „delegiert”, um den Staatsimmobilienfonds zu leiten. Der Fonds begrüßte einen neuen Leiter, aber der Ausschuss ist als eine der wichtigsten und stabilsten Institutionen des Parlaments effektiv gelähmt. Derzeit kämpfen mehrere Einflussgruppen innerhalb des Ausschusses heftig um die Vorherrschaft, und die Arbeitsfortschritte sind ins Stocken geraten.

Gerade aus Sorge vor einem ähnlichen Szenario platzte auch die Ernennung von Denys Maslov, Vorsitzender des Ausschusses für Rechtspolitik des Parlaments, zum Justizminister. Die Führung der präsidentiellen „Einzelnen Mehrheit” blieb hart: „Wenn sogar der Rechtsausschuss ruiniert wird, dann können sich alle gleich auflösen. Die Regierung braucht talentierte Leute, aber das Parlament braucht sie auch. Wir sind nicht mehr bereit, unsere eigenen Leute ins Kabinett zu schicken.”

„Das Parlament auflösen” ist jetzt die gewünschte Option für Selenskyjs Team auf parlamentarischer Ebene. Früher drohte Selenskyj mit der Auflösung des Parlaments, um legislative Prozesse voranzutreiben; heute träumen die Abgeordneten davon, endlich ihren Abgeordnetenstatus loszuwerden.

In den vergangenen Jahren tauchten in den Fluren des Parlaments gelegentlich Nachrichten auf, dass Dutzende von Abgeordneten der Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’ Rücktrittsgesuche eingereicht hatten, aber diese Anträge wurden von Davyd Arakhamia zurückgestellt. Dieser Führer der „Mehrheit” überredete die Abgeordneten ständig, dass die Amtszeit „bald” enden würde. Dieses versprochene „Bald” ist jedoch noch nicht eingetroffen.

Die Abgeordneten hatten große Hoffnungen auf erfolgreiche Verhandlungen und schnelle Wahlen gesetzt. Der Iran-Krieg hat jedoch den Verhandlungsprozess im Modell Ukraine-USA-Russland effektiv zum Stillstand gebracht. Daher sind die meisten von Ukrainska Pravda befragten Parlamentarier überzeugt, dass die Ukraine kurzfristig keine Wahlen abhalten wird.

„Es gibt keine spezifische Frist für wahlbezogene Gesetzgebungen. In den Sitzungen der Arbeitsgruppe Kornienko diskutieren sie verschiedene Szenarien und potenzielle Risiken, aber das ist nur Geschwätz ohne konkrete Ergebnisse,” erklärte ein hochrangiger Vertreter der Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’, zitiert von Ukrainska Pravda.

„Europa sagt: ‚Haltet noch anderthalb bis zwei Jahre durch und kämpft. Wir geben euch Finanzierung.’ Davon beeinflusst, hat Selenskyj die politische Führung angewiesen, Szenarien zu entwickeln, um sicherzustellen, dass die Ukraine in den nächsten Jahren keine Wahlen abhält, und zu planen, wie das Parlament unter solchen Umständen arbeiten kann”, fügte eine weitere Quelle aus Selenskyjs innerem Kreis hinzu.

Die Erwartungen auf das Kriegsende und das Ablaufen der Abgeordnetenmandate sind wie Seifenblasen geplatzt. Die Drohung der Parlamentsauflösung und „Umschlag-Anreize” haben ihre inspirierende Wirkung auf die Abgeordneten verloren. Vielleicht entstehen deshalb verschiedene neuartige Vorschläge, wie z. B. die Verabschiedung eines Gesetzes zur Mobilisierung von Volksabgeordneten. Derzeit wird dies als Witz erzählt. Aber das Niveau der Beamten, die solche Witze machen, ist tatsächlich besorgniserregend.

Keine „Weggefährten” mehr: Warum die Opposition nicht mehr mit ‚Diener des Volkes’ stimmt

Ein „Mobilisierungs”-Anreizschema könnte ein weiteres wirksames Instrument für die Behörden werden, um die Opposition zu kontrollieren. Es klingt etwas barbarisch, aber Selenskyjs Team scheint keine anderen Ressourcen zu haben, um extern Partner zu suchen.Nach dem Vorfall der „umschlagartigen politischen Verfolgung” beendete Timoschenko die Zusammenarbeit zwischen der Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’ und der Partei ‚Batkivshchyna’ (Vaterland).

Laut Ukrainska Pravda gab Julija Wolodymyriwna, als Detectives des Nationalen Antikorruptionsbüros und Mitarbeiter der Spezialisierten Antikorruptionsstaatsanwaltschaft das Parteibüro besuchten, im Gespräch mit Parteibgeordneten Arakhamia die Schuld daran. Angeblich unterdrücken die Behörden die Opposition.

Zuvor tauschte die Führerin von „Batkivshchyna” Stimmrechte gegen verschiedene „Vorteile” ein. Nachdem Timoschenko einen Verdachtsbescheid erhalten hatte, nahmen die Abgeordneten von Batkivshchyna zeitweise sogar nicht mehr an Sitzungen des Koordinierungsausschusses und des Parlaments teil. In dieser Situation ist es einfach unrealistisch, von ihnen zu verlangen, nach der Agenda der Regierungspartei zu arbeiten.

Darüber hinaus machen Timoschenkos lange Ausführungen zur „externen Verwaltung” in verschiedenen Interviews es schwer zu glauben, dass ihre Partei dafür stimmen würde, IWF- oder Ukraine-Fazilitäts-relevante Gesetze zu unterstützen – Gesetze, die nur das stärken würden, was sie als „externe Verwaltung” bezeichnet.

Die Beziehung zwischen der präsidentiellen Fraktion und Petro Poroschenko erlebte nur in der frühen Phase des umfassenden Krieges eine kurze Entspannung. Damals unterstützte die Partei „Europäische Solidarität” aktiv alle Gesetzentwürfe.

Aber Strafverfahren und Sanktionen gegen Poroschenko durch das Staatliche Ermittlungsbüro sowie Versuche, die Partei aus dem Büro in der Lawra-Straße zu vertreiben, nützen offensichtlich nicht der Zusammenarbeit zwischen den politischen Kräften des aktuellen und des ehemaligen Präsidenten.

Und seit der Wahlaufruf von jenseits des Ozeans kam, ist die Erwartung von Brüderlichkeit und Einheit zwischen der Partei „Europäische Solidarität” und der Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’ noch aussichtsloser.

Die Fraktion der Partei „Holos” (Stimme) arbeitet schon lange nicht mehr als einheitliches Ganzes und kann daher nicht einmal ein temporärer Verbündeter der Einzelnen Mehrheit werden.

Daher kann die Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’ derzeit nur auf die Abgeordneten der Partei „Trust” (Vertrauen) und einige Überreste der verbotenen Partei „Oppositionsplattform – Für das Leben” hoffen. Aber selbst wenn sie alle erscheinen, können sie nur ein paar Dutzend Ja-Stimmen liefern. Angesichts der Abstimmungsergebnisse der Plenarsitzung am 10. März reicht diese Unterstützung bei weitem nicht aus, um Gesetze zu verabschieden.

Daher muss entweder der Präsident Kraft und interne Energie bündeln, um mit seiner eigenen Fraktion im Parlament einen Konsens zu erzielen, oder das Land muss sich der von Daniel Getmantsev gewarnten Finanzkatastrophe stellen – und sie könnte noch in diesem Frühjahr eintreffen.

Am 20. Januar 2026 erklärte Selenskyj im Online-Austausch mit Journalisten, dass verschiedene Finanz- und politische Gruppen stets versucht hätten, die parlamentarische Fraktion des Präsidenten zu zerschlagen.

„Aber die Einzelne Mehrheit hat alle Gesetze verabschiedet, die von der EU und der Weltbank gefordert wurden, die für unseren Antrag auf EU-Beitritt entscheidend sind,” betonte der Präsident.

Heutzutage kann Selenskyjs „Regierungskoalition” nicht einmal unterstützende Stimmen für Gesetze sicherstellen, die die finanzielle Lebensader der Nation betreffen, insbesondere nicht für diese Schlüsselgesetze.

Die Rada und sogar das gesamte um Selenskyj aufgebaute Machtsystem erleben die schwerste Krise seit Beginn ihrer Arbeit im Jahr 2019. Die Abgeordneten sind erschöpft und haben die Motivation verloren, in einer „One-Man-Show” die zweite oder dritte Geige zu spielen.

Wie ein Gesprächspartner von Ukrainska Pravda im Hauptgebäude in der Hruschewskyj-Straße scherzte: „Alle sind zu lange eingelegt worden.”

Aber selbst wenn dieses „Gurkenglas” kurz vor dem Platzen des Deckels steht, können Wahlen immer noch nicht abgehalten werden, also gibt es keine Wahl – das einzige legislative Organ muss weiterarbeiten.

„Wie auch immer, wir müssen weiterhin abstimmen, um zu beweisen, dass das ukrainische Parlament tatsächlich existiert. Ist es schwierig? In letzter Zeit ist es außergewöhnlich schwierig geworden. Aber wir haben keine Wahl,” fasste ein hochrangiger Beamter der Partei ‚Diener des Volkes’ im Austausch mit Ukrainska Pravda zusammen.

Analysis of Ukrainian Political Crisis & Parliamentary Collapse

Investigation by Ukrainska Pravda

According to Ukrainska Pravda: Investigation Reveals How “Envelope Politics” Persecution Led to the Collapse of Zelenskyy’s Parliamentary Control

An investigation by Ukrainska Pravda reveals how the chilling effect triggered by the investigation into “envelope politics” (cash bribes for votes) has led to the collapse of President Zelenskyy’s faction’s control over parliament. Analysis points out that the structural tension between anti-corruption mechanisms and legislative efficiency is causing Ukraine to face a dual crisis: stagnation in IMF reforms and a fiscal cliff. This reflects deep institutional dilemmas within the wartime and post-war governance systems.![Image]

Ukraine has just survived the harshest winter in its history and should have been able to catch its breath in early spring. But unfortunately, that is unlikely. Since the outbreak of the full-scale war, the danger of economic collapse has never been so imminent.

The country is entering its most difficult spring with an unbalanced economy and a state almost entirely dependent on the timeliness of external borrowing. Literally speaking, the ability to continue fighting successfully depends on whether the authorities can maintain economic controllability and financial stability.

Therefore, the work of Ukraine’s political leadership must be subordinate to the goal of finding sources of funding for the state.

First, this involves unlocking the €90 billion loan provided by the EU.

Second, rapidly meeting the conditions for IMF assistance and the “Ukraine Facility” program.

The first task is extremely difficult because Kyiv has limited influence over Hungary, which is deeply entrenched in election politics and Ukrainophobia. Meanwhile, the “homework” involving the reform agenda should have been implemented without delay.But as they say, there is a problem—the only body capable of passing the necessary legislative reforms, the Verkhovna Rada, is crumbling before everyone’s eyes.

“On March 5, President Zelenskyy held a large joint meeting with the government, the Presidential Office, and parliament. After the meeting, the Rada leadership had a several-hour conversation with Kachka (Deputy Prime Minister for European Integration). The Deputy Prime Minister proposed: ‘I have a grand conception—submit 300 European integration bills to parliament.’ Stefanchuk responded: ‘Taras, forget it. You have the first cluster (of EU accession negotiations)—submit even one (!) bill, and let’s try to push it through. Why let this ‘machine’ idle 300 times?’ ” — recounted an eyewitness to the officials’ dialogue.

In fact, this contrast between the massive scale of urgent problems and the actual ability of the presidential team to push resolutions through parliament accurately depicts the disaster situation the authorities are approaching. The entire country is consequently falling into crisis.

It all started with the reckless attack on anti-corruption agencies last July, in which the Verkhovna Rada was assigned the role of executor.

Following the “Mendych scandal,” the exposure of numerous corruption cases within the Presidential Office and government, and the cloud of suspicion over MPs’ “envelope incentives,” the once powerful monopolistic majority has shrunk to a precarious size.

Furthermore, after the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) launched an “envelope-style political persecution” operation against Yulia Tymoshenko, the Servant of the People party also lost the opportunity to strive for “external allies.”👇🏻

Systematically Dedicated to “Crushing the Majority”: Allegations of Tymoshenko “Buying Hearts”

The result is that sensitive bills crucial for IMF cooperation repeatedly fail in votes. Even with all its might, the Servant of the People party can barely scrape together 120 votes, far from the required 226 votes.Why has President Zelenskyy’s party fallen into a state of semi-disintegration? Does it still have the ability to regroup MP forces? Can Tymoshenko and other “opposition” figures return to a constructive track? More importantly, can the country avoid economic collapse without external aid?

The Missing Core, or the “No Longer Majority” Dilemma

The so-called “single majority” actually no longer holds a majority of seats. In the early stages of the invasion, MPs united, and parliament functioned at full capacity. But as this large-scale war continued year after year, the situation gradually deteriorated.Some elected representatives are scattered in the “Uzhhorod boiler” (a slang term implying disarray), some have fled abroad, and others have been expelled from factions.

Instability within the Servant of the People party has always existed. But despite this, the faction always maintained a stable core force. Before the war and during the “Mendych” incident, its core member size remained around 170 to 180.

In addition, the Servant of the People party could also pull in oligarch Andriy Verevsky’s “Trust” group, which was always willing to provide about 20 loyal votes. There was also an opportunity to reach an agreement with the “For the Future” group led by Ihor Palitsa. Although their voting discipline was poor, they could still gather 10 to 15 votes when necessary.

Plus those votes called “captive votes” by MPs themselves, coming from the oligarch camps of Serhiy Lyovochkin and Dmytro Firtash, and the remnant “Opposition Platform - For Life” party group led by Vadym Stolar.

Yulia Tymoshenko’s faction was also always looking for opportunities to exert influence. They traded voting rights—sometimes for extra speaking time, sometimes for airtime on the “United Marathon” program, and sometimes to demand law enforcement agencies reduce investigations into their members.

In short, despite having 180 seats, the Servant of the People party was always able to vote according to the agenda issued by the Presidential Office. Until the summer of 2025, when the situation took a sharp turn for the worse. At that time, the Presidential Office attempted to launch a small-scale anti-corruption revolution in Ukraine but ultimately suffered a disastrous defeat in the “Cardboard Maidan” incident.

In this war between the Presidential Office and anti-corruption agencies, the Verkhovna Rada merely acted as the executor of the “criminal plan.” However, even though the President successfully restored his support rate after that scandal, parliament never recovered from the blow.

When NABU questioned the “envelope incentives,” especially targeting figures close to Yuriy Kisyel, an MP from the “Batkivshchyna” (Fatherland) party, the already fragile “single majority” structure began to shake even more violently.

The Servant of the People party now complains that the accusations against Kisyel and other involved personnel mention that they received payments for voting to approve “meaningless intergovernmental agreement ratification cases.”

“During the entire war, the Verkhovna Rada only conducted two votes involving ‘vested interests’: the Soybean Amendment and the Khmelnytskyi Nuclear Power Plant Equipment Procurement Case. That’s it. At this time, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau suddenly intervened, claiming MPs received bribes for approving international agreements. This is complete nonsense. Everyone understands that MPs are under pressure because of the war between the President and anti-corruption agencies. Okay, let them resolve internal contradictions first, then we will vote.” — explained an influential Servant of the People MP regarding the faction’s indignation.

MPs shyly avoided the fact that the international agreement ratification case was only one of the voting items where bribed MPs received “envelope incentives.” But the key is that there is indeed a general consensus within the ruling faction on the above interpretation of the anti-corruption agency’s actions.

Since the MP salary increase last December, the demand for envelope cash subsidies has naturally disappeared. Now, as parliamentary sources assured Ukrainska Pravda, no one is bribing Servant of the People MPs anymore. But they are no longer participating in votes either.

“We have an excellent National Anti-Corruption Bureau and Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office—they are heroes. As for now we cannot pass any laws regarding fund mechanisms or the IMF—those are trivial details. No one cares about these.” — sarcastically remarked an MP from the Servant of the People leadership.

“Many people say: ‘I’d rather vote for nothing than have the National Anti-Corruption Bureau come knocking.’ The core members of the parliamentary faction have dropped to 110-120. How to vote on complex bills—there is simply no solution. After all, the NABU people won’t come vote for us.” — added a fellow MP wearily, preferring to push all the blame onto those who exposed the “envelopes” rather than those who filled them.

The votes in parliament on March 10 seemed to only confirm what Ukrainska Pravda sources said. MPs were supposed to vote on the sensitive bill regarding the so-called digital platform tax and several government draft laws.

But even though the digital platform tax bill only required a first reading vote, it still failed to pass. Among them, controversial clauses regarding taxing international parcels under €150 and levying VAT on individual entrepreneurs were originally planned to be added to the bill before the second reading.

Even under these relaxed conditions, the bill and the Servant of the People party’s government social projects could only gain 120-130 votes support.

However, in the March 10 vote, one must look not only at the bills that failed but also examine those that received support. Otherwise, a complete picture cannot be obtained.

The first two votes (approving the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions and authorizing the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense to use dedicated radio frequencies) received wide support in the parliament hall and passed smoothly. The Servant of the People party cast 183 and 170 votes in favor respectively. But just 6 minutes later, during the “Digital Platform Tax Case” vote, this support potential mysteriously disappeared.

“No one understands how this can be: we have to collect money from every parcel, be the villains, while Yulia and the President want to distribute their new round of thousands of hryvnias, eSupport, etc. Now we have to take the blame for them, will the President sign afterwards? We’ve encountered this before, where he directly washes his hands and doesn’t sign.” — explained a Servant of the People MP involved in obstructing the IMF bill.

“The leadership thinks he can continue to issue ideas at will, and we will vote in support without objection. Since we belong to the same team, please share public responsibility with us. Even just communicating with MPs would be good. But for us, the easier thing to do is cancel certain people’s routine benefits, struggle hard to strive for a pitiful 1 billion hryvnias for housing for internally displaced persons. Then yet can allocate 10 billion funds casually for some absurd projects—like a health checkup plan for people over 40—just because these sound glamorous in evening TV addresses.” — a Ukrainska Pravda source angrily added regarding the internal situation of the Servant of the People party.

The presidential faction complains of another problem—there is “purposeful work” being done against Servant of the People.

“Before every important vote, 15-20 of our MPs suddenly disappear. They were originally present—then suddenly vanished. These people are not from a fixed group or organized faction, just some unrelated random personnel. We are investigating the mastermind behind this because this situation appears very suspicious,” — revealed a Servant of the People leadership figure.

Internal sources from the Servant of the People party said they suspected this was an action taken by Poroshenko or Tymoshenko to dismantle the ruling coalition. Especially since Tymoshenko herself had been recorded by NABU for similar behavior in the past.

However, Ukrainska Pravda’s interlocutors in the parliament leadership and factions are not too clear about what those trying to split the Servant of the People party actually want.

“Neither the constitution nor the law cites the absence of a coalition as grounds for the government’s resignation or any other termination of its powers. Nor is it a reason for the early dissolution of parliament. Firstly, it is no longer possible to talk about any early dissolution of parliament because the parliament is already operating overtime. Secondly, during martial law, parliament simply cannot be dissolved. So both the government and parliament will take action. It’s a futile effort,” said a leadership figure from the ‘Servant of the People’ party, shrugging helplessly.

How Parliament Survives Without “Sweeteners” When There Is No Motivation

“Parliament has been operating for nearly 7 years. I’m not saying it’s difficult and exhausting. But after such a long time, even cucumbers in a barrel would ferment and turn sour,” complained a high-ranking official from the ‘Servant of the People’ party.A parliamentary source from Ukrainska Pravda admitted that the 9th Convocation has exhausted its potential. Nowadays, even the smallest factor of instability can lead to internal collapse.

For example, the parliament recently “delegated” Dmytro Natalukha, Chairman of the Economic Committee, to manage the State Property Fund. The fund welcomed a new head, but the committee, as one of the key and most stable institutions of parliament, is effectively paralyzed. Currently, multiple influence groups within the committee are engaged in a fierce struggle for dominance, and work progress has stalled.

It was precisely out of concern for a similar script that the appointment of Denys Maslov, Chairman of the Parliament’s Legal Policy Committee, as Minister of Justice also fell through. The leadership of the presidential “Single Majority” took a hard line: “If even the Legal Committee is wrecked, then everyone might as well disband. The government needs talented people, but parliament needs them too. We are no longer willing to send our own people into the Cabinet.”

“Dissolving parliament” is now the most desired option for Zelensky’s team at the parliamentary level. Previously, Zelensky threatened to dissolve parliament to push legislative processes; nowadays, what MPs dream of is finally getting rid of their MP status.

In past years, news occasionally surfaced in the parliamentary corridors that dozens of ‘Servant of the People’ party MPs had submitted resignations, but these applications were shelved by Davyd Arakhamia. This leader of the “Majority” constantly persuaded MPs that the term would end “soon.” However, this promised “soon” has yet to arrive.

MPs had pinned high hopes on successful negotiations and swift elections. However, the Iran war has effectively stalled the Ukraine-US-Russia model negotiation process. Therefore, most parliamentarians interviewed by Ukrainska Pravda are convinced that Ukraine will not hold elections in the short term.

“There is no specific deadline for election-related legislation. At the Kornienko working group meetings, they discuss various scenarios and potential risks, but this is just chatter without concrete results,” explained a high-ranking figure from the ‘Servant of the People’ party, cited by Ukrainska Pravda.

“Europe says: ‘Hold on and fight for another year and a half to two years. We will give you funding.’ Affected by this, Zelensky has instructed the political leadership to develop scenarios to ensure Ukraine does not hold elections for the next few years, and to plan how parliament operates under such circumstances,” added another source from Zelensky’s inner circle.

Expectations for the end of the war and the expiration of MPs’ terms have burst like bubbles. The threat of dissolving parliament and “envelope incentives” have lost their inspiring effect on MPs. Perhaps this is why various novel proposals are emerging, such as passing a bill on mobilizing people’s deputies. Currently, this is told as a joke. But the level of officials making such jokes is actually worrying.

No More “Fellow Travelers”: Why the Opposition No Longer Votes with ‘Servant of the People’

A “mobilization” incentive scheme could become another effective tool for authorities to control the opposition. It sounds somewhat barbaric, but Zelensky’s team seems to have no other resources to seek partners externally.After the “envelope-style political persecution” incident, Tymoshenko ended the cooperation between the ‘Servant of the People’ party and the ‘Batkivshchyna’ (Fatherland) Party.

According to Ukrainska Pravda, when detectives from the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and staff from the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office visited Yulia Volodymyrivna’s party office, she blamed Arakhamia for this while talking to party MPs. Allegedly, the authorities are suppressing the opposition.

Previously, the leader of ‘Batkivshchyna’ exchanged voting rights for various “benefits.” After Tymoshenko received a suspicion notice, Batkivshchyna MPs even stopped attending coordination committee and parliament meetings for a time. In this situation, asking them to work according to the ruling party’s agenda is simply unrealistic.

Furthermore, Tymoshenko’s lengthy expositions on “external management” in various interviews make it hard to believe her party would vote to support IMF or Ukraine Facility-related bills—bills that would only strengthen what she calls “external management.”

The relationship between the presidential faction and Petro Poroshenko only saw a brief thaw during the early stages of the full-scale war. At that time, the ‘European Solidarity’ Party actively supported all draft laws.

However, criminal cases and sanctions against Poroshenko by the State Bureau of Investigation, as well as attempts to evict the party from the Lavra Street office, obviously do not benefit cooperation between the political forces of the current and former presidents.

And since the call for elections came from across the ocean, expecting brotherhood and unity between the ‘European Solidarity’ Party and the ‘Servant of the People’ Party is even more futile.

The ‘Holos’ (Voice) Party faction has long ceased to operate as a unified whole, so it cannot even become a temporary ally of the Single Majority.

Therefore, all the ‘Servant of the People’ Party can currently count on are the ‘Trust’ Party MPs and some remnants of the banned ‘Opposition Platform - For Life’ Party. But even if they all show up, they can only provide a few dozen affirmative votes. Considering the voting results of the plenary session on March 10, this support is far from enough to pass bills.

Therefore, either the president can condense/gather strength and internal energy to reach a consensus with his own faction in parliament, or the country will have to face the financial disaster warned by Daniel Getmantsev—and it may arrive this spring.

On January 20, 2026, Zelensky stated during an online exchange with journalists that various financial and political groups have always attempted to dismantle the president’s parliamentary faction.

“But the Single Majority voted through all laws required by the EU and the World Bank, which are crucial for our application to join the EU,” the president emphasized.

Nowadays, Zelensky’s “ruling coalition” cannot even ensure supportive votes for bills concerning the nation’s financial lifeline, especially those key bills.

The Rada, and even the entire power system built around Zelensky, is experiencing the most severe crisis since it began operating in 2019. MPs are exhausted and have lost the motivation to act as the second or third lead in a “one-man show.”

As a interlocutor from Ukrainska Pravda inside the main building on Hrushevsky Street jokingly put it: “Everyone has been pickled too long.”

But even if this “pickle jar” is on the verge of exploding, elections still cannot be held, so there is no choice—the only legislative body must continue to operate.

“Anyway, we still have to continue voting to prove that the Ukrainian Parliament indeed exists. Is it difficult? It has become exceptionally difficult recently. But we have no choice,” summarized a high-ranking official from the ‘Servant of the People’ Party during an exchange with Ukrainska Pravda.

“Denn die solle für uns noch eineinhalb bis zwei Jahre kämpfen?”

Also nein - des is ja, also…

Wie kann denn das sein?

edit: Originalzitat - secondary source:

“The Europeans said: ‘Fight for another year and a half or two. We will give you money.’ Under their influence, Zelensky gave the political leadership the task of developing a scenario according to which there would be no elections in Ukraine for several more years and how the Rada would work in such a situation,” said an interlocutor among influential representatives of Zelensky’s team.

src: click

Original source: click (Ukrainska Pravda)

Claude Sonnet translation of the relevant text passages -- Deepseek to follow as a backup.

German Translation

Die Option der „Auflösung” [des Parlaments] ist derzeit die am sehnlichsten erwartete für den parlamentarischen Flügel des Ze!Teams. Früher motivierte Selensky die Rada mit Auflösungsdrohungen. Nun träumen die Abgeordneten davon, endlich ihre Mandate loszuwerden.

In den letzten Jahren wurden hinter den Kulissen des Parlaments gelegentlich Dutzende von Rücktrittsanträgen der „Diener des Volkes” diskutiert, die David Arachamia nicht vorantreibt. Der Chef der „Mono-Minderheit” überzeugt die Parlamentarier ständig davon, dass die Amtszeit „bald” ende. Doch das versprochene „Bald” tritt einfach nicht ein.

Die Abgeordneten hatten große Hoffnungen auf erfolgreiche Verhandlungen und schnelle Wahlen gesetzt. Doch der Krieg im Iran hat den Verhandlungsprozess im Format Ukraine–USA–Russland faktisch auf Eis gelegt. Daher sind die meisten Gesprächspartner der Ukrainska Prawda in der Rada überzeugt, dass es in der Ukraine so bald keine Wahlen geben wird.

„Es gibt keine konkreten Fristen für die Ausarbeitung von Wahlgesetzen. In den Sitzungen der Arbeitsgruppe von Kornienko werden verschiedene Optionen und mögliche Risiken besprochen, aber es ist Small Talk ohne konkrete Ergebnisse”, erklärt einer der Spitzenvertreter der „Diener des Volkes” gegenüber UP.

„Die Europäer sagten: ‚Kämpft noch anderthalb bis zwei Jahre. Wir werden euch Geld geben.’ Unter ihrem Einfluss hat Selensky der politischen Führung die Aufgabe erteilt, ein Szenario zu entwickeln, bei dem es in der Ukraine noch mehrere Jahre lang keine Wahlen gibt und wie die Rada in einer solchen Situation funktionieren soll”, fügt ein weiterer Gesprächspartner unter einflussreichen Vertretern des Ze!Teams hinzu.

Die Hoffnungen auf ein Kriegsende und die Niederlegung der Abgeordnetenmandate erwiesen sich als vergeblich. Die Einschüchterung durch Auflösung und die „Umschlagmotivation” [d. h. Bargeldanreize] haben ihre aufmunternde Wirkung auf die Abgeordneten verloren.

Vielleicht sollte man gerade hier nach dem Ursprung verschiedener extravaganter Ideen suchen – wie etwa die Verabschiedung eines Gesetzes zur Mobilisierung von Parlamentsmitgliedern.

Vorerst wird dies als Witz erzählt. Doch das Niveau der Amtsträger, die sich solcher Witze bedienen, ist tatsächlich beunruhigend.

English Translation

The option of “dispersing” [parliament] is currently the most desired for the parliamentary wing of Ze!Team. Previously, Zelensky motivated the Rada with threats of dissolution. Now, deputies are dreaming of finally being rid of their mandates.

Over the last few years, behind the scenes of parliament, dozens of resignation statements from “Servants of the People” have occasionally been discussed, which David Arakhamia refuses to put in motion. The head of the “mono-minority” constantly convinces parliamentarians that the term will “soon” be over. But the promised “soon” never arrives.

Deputies had placed great hopes on successful negotiations and quick elections. But the war in Iran has effectively put the negotiation process in the Ukraine–USA–Russia format on pause. Therefore, the majority of Ukrainska Pravda’s sources in the Rada are convinced that elections in Ukraine will not happen anytime soon.

“There are no specific deadlines for developing legislation on elections. At the meetings of Kornienko’s working group, various options and possible risks are being discussed, but it’s small talk with no concrete results,” one of the top figures in “Servants of the People” explains to UP.

“The Europeans said: ‘Fight for another year and a half to two years. We will give you money.’ Under their influence, Zelensky tasked the political leadership with developing a scenario under which Ukraine will have no elections for several more years, and how the Rada would function in such a situation,” adds another source among influential representatives of Ze!Team.

Hopes for the end of the war and the laying down of deputy mandates proved to be in vain. Intimidation by dissolution and “envelope motivation” [i.e., cash incentives] have lost their encouraging effect on deputies.

Perhaps it is here that one should look for the origin of various kinds of extravagant ideas — such as, for example, the adoption of a law on the mobilization of parliament members.

For now, this is being told as a joke. But the level of officials who resort to such jokes is, in fact, alarming.

edit: Dazu Kaja Kallas heute:

Spalter!

src: click

edit: Deepseek v3.2 Translation added.

Still not good enough. But eh, there you have it.

German Translation:

Die Option der “Auflösung” ist derzeit die von der parlamentarischen Flügel der Ze!Team am meisten gewünschte. Zuvor hatte Selenskyj die Rada mit Auflösungsdrohungen motiviert. Nun träumen die Abgeordneten davon, endlich ihre Mandate loszuwerden.

In den letzten Jahren wurden in den Parlamentskorridoren geleglich Dutzende Anträge von Abgeordneten des “Diener des Volkes” auf Niederlegung ihrer parlamentarischen Befugnisse diskutiert, denen David Arachamia jedoch keinen Schwung verleiht. Das Oberhaupt der “Monomehrheit” überzeugt die Parlamentarier ständig, dass die Kadenz “bald” ende. Aber das versprochene “bald” will nicht eintreten.

Große Hoffnungen setzten die Abgeordneten auf erfolgreiche Verhandlungen und schnelle Wahlen. Doch der Krieg im Iran hat den Verhandlungsprozess im Format Ukraine–USA–Russland praktisch pausiert. Daher sind die meisten Gesprächspartner der UP in der Rada überzeugt, dass es in der Ukraine in absehbarer Zeit keine Wahlen geben wird.

“Es gibt keine konkreten Fristen für die Ausarbeitung einer Gesetzgebung zu Wahlen. Auf den Sitzungen der Arbeitsgruppe bespricht Kornijenko verschiedene Optionen und mögliche Risiken, aber das ist Smalltalk ohne konkrete Ergebnisse”, erklärt einer der Top-Vertreter der “SN” der UP.

“Die Europäer sagten: ‘Kämpft noch anderthalb bis zwei Jahre weiter. Wir geben euch Geld.’ Unter ihrem Einfluss gab Selenskyj der politischen Führung die Aufgabe, ein Szenario zu entwickeln, nach dem es in der Ukraine noch mehrere Jahre lang keine Wahlen geben wird und wie die Rada in einer solchen Situation arbeiten würde”, fügt ein anderer Gesprächspartner unter einflussreichen Vertretern der Ze!Team hinzu.

Die Hoffnungen auf ein Kriegsende und die Niederlegung der Abgeordnetenmandate haben sich als vergeblich erwiesen. Einschüchterung durch Auflösung und “Kuvert-Motivation” haben ihre aufmunternde Wirkung auf die Abgeordneten verloren.

Vielleicht sollte man hier den Grund für das Auftauchen verschiedenster extravaganter Ideen suchen, wie zum Beispiel die Verabschiedung eines Gesetzes zur Mobilisierung von Abgeordneten.

Im Moment wird das als Witz erzählt. Aber das Niveau der Amtsträger, die zu solchen Witzen greifen, ist in der Tat beunruhigend.

English Translation:

The option of “dissolving” is currently the most desired by the parliamentary wing of Ze!Team. Previously, Zelenskyy motivated the Rada with threats of dissolution. Now, the deputies are dreaming of finally getting rid of their mandates.

For the last few years, in the parliamentary corridors, dozens of applications from “Servant of the People” MPs to resign their parliamentary powers have been occasionally discussed, but these are not given movement by David Arakhamia. The head of the “mono-majority” constantly convinces parliamentarians that their term will end “soon.” But the promised “soon” never comes.

The deputies placed great hopes on successful negotiations and quick elections. But the war in Iran has essentially put the negotiation process in the Ukraine–USA–Russia format on pause. Therefore, most of UP’s interlocutors in the Rada are convinced that there will be no elections in Ukraine in the near future.

“There are no specific deadlines for drafting legislation on elections. At the working group meetings, Korniienko discusses various options and possible risks, but it’s small talk without concrete results,” explains one of the top officials of “SN” to UP.

“The Europeans said: ‘Fight for another one and a half to two years. We will give you money.’ Under their influence, Zelenskyy tasked the political leadership with developing a scenario under which there would be no elections in Ukraine for several more years and how the Rada would work in such a situation,” adds another interlocutor among influential representatives of Ze!Team.

Hopes for the end of the war and the resignation of parliamentary powers have proven futile. Intimidation with dissolution and “envelope motivation” have lost their encouraging effect on the deputies.

Perhaps it is here that one should look for the reason for the emergence of various kinds of extravagant ideas, such as, say, passing a law on the mobilization of MPs.

For now, this is told as a joke. But the level of officials who resort to such jokes is actually alarming.

Deepseek Contextual note:

Contextual Note: The text discusses Ukrainian domestic politics, referring to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy (“Зеленський”), his party “Servant of the People” (“Слуга народу” / “SN”), and the parliamentary chairman David Arakhamia (“Давид Арахамія”). The term “Ze!Team” is a common label for Zelenskyy’s political team and allies. The “war in Iran” mentioned is likely a geopolitical reference point within the article’s narrative. The translations aim to preserve the original tone and specific political terminology.

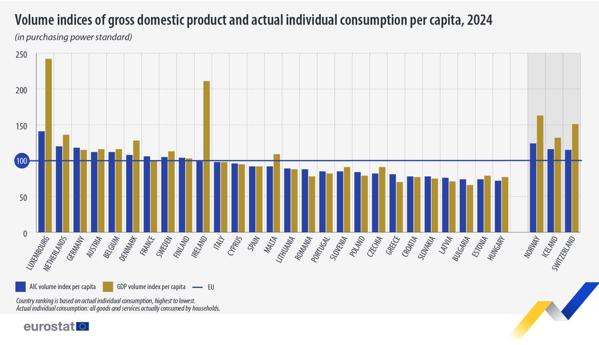

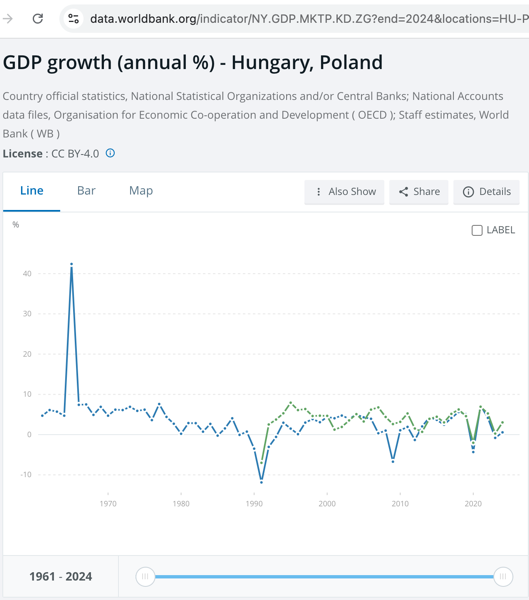

Korrelieren sie doch mal folgende Zahlen…

Ich hasse es so sehr von Idioten umgeben zu sein.

Was haben uns die Römer schon gebracht…

src: click

Ungarn Letzte, Ungarn Letzte!

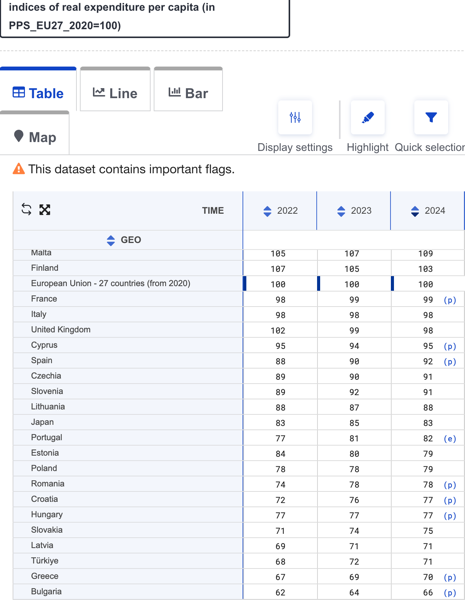

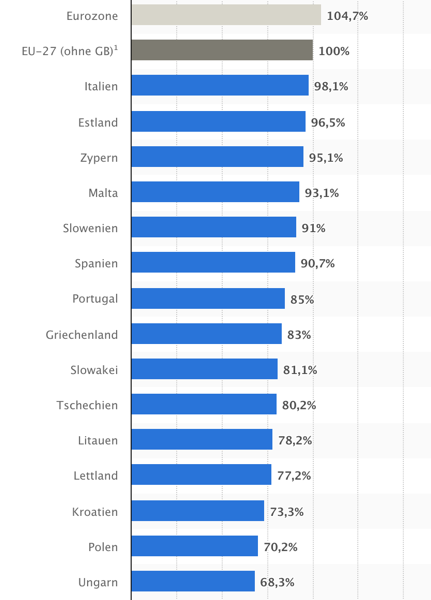

Indices of real expenditure per capita (in PPS EU 27)

src: click

Ungarn 77% of EU 2020 average, Poland 79% of EU 2020 average.

(Ungarn nicht Letzte.)

Huch! Wie ist den das möglich!

Oh, EU Preisniveauindex!

src: click

Und Huch, den zweiten Faktor haben sie schon gesehen aber nicht realisiert!

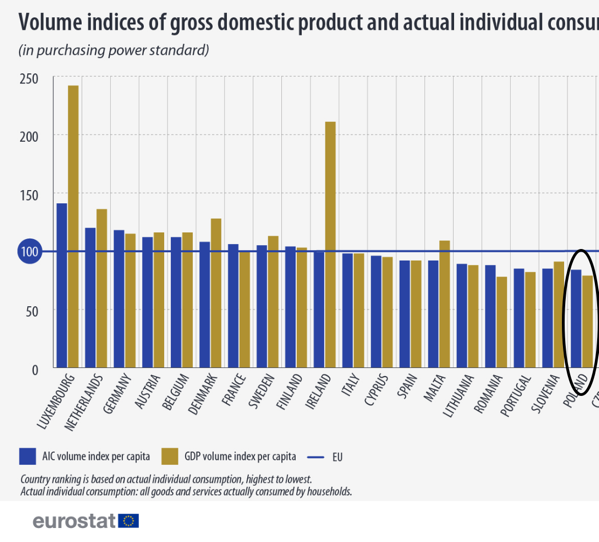

Defecit spending in Polen.

AIC (actual individual consumtion) ist in Polen höher als das GDP.

Jahaa! Aber die Korruption in Ungarn, wie kannst du nur!

AIC to GDP ratio liegt auf dem selben Niveau wie Belgien. Also Ungarn ist quasi eine Gesellschaft unter funktionierender Korruption an der auch die Opposition nicht viel ändern wollen wird (Magyar war die selbe Partei fährt die selbe Strategie, nutzt die selben Parolen, …) -- aber - auf die Richtung kommts eben an.

src: click

Warum muss Orban nochmal abgewählt werden?! Ach ja, wegen seiner schlechten Ökonomischen Performance seit 2013…

Moment, seit 2013 die idente Wirtschaftliche Entwicklung wie Polen?

src: click

Also bis auf die letzten Kriegsjahre, als plötzlich die Ölversorgung wackelig wurde?

Kann das bitte jemand in gutem Deutsch für mich zusammenfassen?

Klar.

Sie werden hier schon wieder emotional manipuliert was das Zeug hällt.

Also - das Wachstum in Polen hängt an US Finanzierung und EU Krediten die sauberer abgefragt werden als in Ungarn, während Ungarn von der EU seit acht Jahren für politische Verfehlungen “soft sanktioniert” wurde.

Besonders deutlich wird das am Einbruch des Wachstums in Krisenjahren wie 2012 oder 2020 in denen Ungarn nicht die selben Hilfsmittel ausschöpfen konnte wie Polen.

Der aktuelle Konsum in Polen ist kreditfinanziert, aber das funktioniert ja, weil die Wachstumsperspektive dank US Investoren und deutschen Unternehmen die dort die Fertigung aufbauen gut ist - und im Energie instabilen Ungarn schlecht.

src: click

Investment growth ist in Polen mittlerweile auch scheiße, weil vor allem geopolitisch getrieben. Da schaut kaum ein ROI raus.

Also was war jetzt noch mal das grobe Vergehen von Orban?

Die zwei Prozent niedrigeres Wohlstandsniveau, das Polen durch overconsumption hällt?

Dass Russland in Krisenzeiten die Hilfszahlungen weniger schnell zugeschossen hat wie die EU, und Orban daher schlechter durch Krisen gekommen ist?

Die Energieunsicherheit - die einzig und allein Selenskyj hergestellt hat?!

Die Demographie, die ebenfalls in Polen etwas besser ist?

Jaja, sie sehen schon, unsere ungarische PR Familie im Standard wählt jetzt Magyar, weil “Magyar liegt die Gen Z am Herzen”!

Wenn die Propaganda nur aufhörn würd…

Auf dem Weg in die gemäßigtere Autokratie…

Ich hab nur Angst, dass Europa demnächst mit einer Stimme spricht, und die Stimme dumm wie die Nacht, aber ideologisch wie ein Standard Reporter ist.

Wenns nicht so einfach wäre ganze Bevölkerungen zu manipulieren…

Und was sind derweil die Länder mit den wirklichen Einkommensungleichheiten in der EU (AIC vs GDP)?

Luxenburg

Niederlande

Dänemark

Schweden

Irland

Malta

Ok, aber das ist AIC to GDP, nicht Gini.

Machen wir Gini coefficient, ok? (Lower is better.)

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?end=2024&start=1963&view=chart&year=2024

Luxenburg 33.6

Niederlande 25.7

Dänemark 29.9

Schweden 29.3

Irland 29.0

Malta 34.6

Polen 28.5

Ungarn 30.6

Lower is better.

Also ganz klar, Orban muss weg.

Germany 32.4

Austria 31.2

Wenn du Bevölkerungen nicht so einfach manipulieren könntest…

edit: Es gibt aber natürlich auch wieder gute Nachrichten. Endlich wissen wir, wozu der UN Sicherheitsrat gut ist.

src: click

Böser Iran! Böse!

Endlich haben wir sie institutionell, die EU der derrangierten christlich sozialisierten, Großfamilien Kirchengänger.

src: click

Dasch is der Preis für die Abhängischkeit - Gott wird sie alle richten, am Tage des jüüüngsten Gerichts - für ihr amoralisches Walten -- meine Ekerln wollten ja Solar, aber die Kinder wollten sie mir nicht jede Woche vorbeibringen, …

Sorry, was war das Thema?!

Ach ja, - die Zukunftsperspektive der EU…

Nun -

Der Ausbau der Solarenergie in Deutschland hat sich im vergangenen Jahr verlangsamt. Trotz politischer Zielvorgaben und staatlicher Fördermaßnahmen.

Dasch ist der Preisch für unsere Unabhängischkeit.

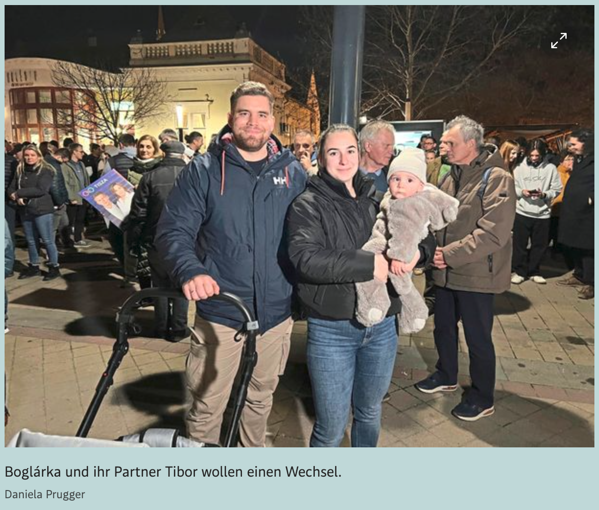

Sehen sie, unsere Qualitätszeitungen sagen uns Boglarka und ihr Partner Tibor wollen auch schon ganz dringend wieder zu uns in die Kirche --

src: click

sie haben sich das mit reiflicher Unterstützung des Standard gut überlegt, weil sie -

Change wollen.

Das ist der Preis für die Unabhängischkeit, …

Na gut, die Demokratien werden schon richtig liegen. Und nach nur 8 Jahren des Versagens haben sich die Alpbach Deplatformer ihren ersten Deplatforming Sieg von Weltrang - ok europäischer Bedeutung nun wirklich verdient.

Die Feste werden großartig ausfallen.

Perspektivisch fast so geil wie Polen die einfach nur den Krieg verlängern wollen, solange ihre Wirtschaft stärker wächst als die der restlichen EU.

Endlich alle Demokraten gemeinsam in der Kirche.

Ich freu mich.

Oh die Boglarka und ihr Partner Tibor haben ein Baby? Das wird sich freun..

Endlich Demokratie leben.

Respekt, Freiheit, und…

Was er an Magyar schätzt? “Mir gefällt, dass er auch junge Leute wie mich einbezieht, die Generation Z.”

Das ischt der Preisch.…

Gut, die NZZ ist gerade auf VOLLE KRAFT ZURÜCK umgeschwenkt, aber was hat das schon zu bedeuten, die is eben nicht bereit zu zahlen den Preis, …

src: click

Sauhaufen. Verdammte Schweizer.

Zuwanderer und Bodenbesitzer profitieren

Swiss Economics hat die Ecoplan-Zahlen analysiert. Dabei zeigt sich: Der prognostizierte BIP-Rückgang von 4,9 Prozent basiert primär auf der Annahme, dass bei einem Wegfall der Bilateralen I – und somit auch der Personenfreizügigkeit – bis 2045 rund 340 000 Personen weniger in die Schweiz einwandern und die Zahl der Grenzgänger um 45 000 sinkt. Das geschätzte BIP-Minus sei daher zum grössten Teil mit dem ausbleibenden Einkommen dieser nicht zugereisten Zuwanderer und Grenzgänger zu erklären, betont die Studie.Lässt man diesen Mengeneffekt ausser acht und berücksichtigt die Auswirkung für die bestehende Wohnbevölkerung, schmilzt der BIP-Rückgang auf nur noch 0,9 Prozent. Da sich dieser Wert auf fast zwei Jahrzehnte verteilt, ist der Effekt laut Swiss Economics minimal. Auch der von Ecoplan berechnete Einkommensverlust von 2500 Franken wird infrage gestellt, da in diesem Betrag die von Schweizern im Ausland erwirtschafteten Kapitalerträge unberücksichtigt seien. Korrigiere man diesen Fehler, sei auch der Einkommenseffekt vernachlässigbar.

Na die werden sich freuen die Kleinfamilien Ungarn, wenn ihre Wohnkosten steigen.

Aber dafür können sie ja auch - in die EU exportieren! Achso, das können sie ja schon, … Gut.

Dasch ist der Preis.

Diese Autokraten, … ständig nur am Energiekosten senken…

Wobei, vieleicht wird Ungarn das neue Österreich. Sie wissen schon die Brücke ins.. Dings!

edit: Puh! Noch mal die Kurve gekriegt!

src: click

US-Finanzminister Scott Bessent erklärte, die Genehmigung solle „die globale Reichweite des bestehenden Vorrats erhöhen“.

The what now?

Keine Angst, die Tanker kommen eh nicht an, die nimmt ja alle die EU auf hoher See hoch.