[Transkript des Videos, siehe weiter unten.]

Vier interviews, drei leicht divergierende Erzählungen, ist eigentlich ein guter Schnitt.

Beginnen wir am Beginn.

02.04.: Profil veröffentlicht ein Interview mit dem rusischen Botschafter in Österreich, in dem der unter anderem folgendes zu Protokoll gibt:

profil: Wer hat denn die Krankenhäuser bombardiert?

Ljubinskij: Es gibt Belege, dass es überhaupt kein Bombardement war, sondern eine Explosion. Die Ukrainer platzieren Sprengsätze.

src: click

Auf welche Krankenhäuser man sich bezieht wird aus dem interview heraus nicht eindeutig klar.

Darauf hin geht eine öffentlich geführte Mediendiskussion (Twitter) los, ob man solche Interviews überhaupt veröffentlichen dürfe. Höhepunkt -

Armin Wolf schrieb, er sei „wirklich unsicher“, er habe „selten (nie?) ein so verlogenes Interview gelesen“, und stellte die Frage: „Soll man ein Interview, das nur aus offensichtlichen Lügen besteht, drucken?“

src: click

Worauf das Profil am 04.04. eine Rechtfertigung veröffentlicht:

In diesem Gespräch legt Ljubinskij die russische Position dar, und die besteht zu einem nicht unbeträchtlichen Teil aus wüsten Behauptungen: So sagt er, dass nicht etwa die russischen Streitkräfte für die Zerstörung der ukrainischen Krankenhäuser verantwortlich sein, sondern vielmehr die Ukrainer selbst Sprengsätze in ihren eigenen Krankenhäusern und Theatern platziert hätten.

Das ist ein abenteuerlicher Vorwurf. Und es ist nicht die einzige dreiste Verdrehung der Realität. Das Interview geriet so zu einem hitzigen Streitgespräch, in dem ich versucht habe, mit meinen Fragen und Gegenreden klarzumachen, wie unglaubhaft und abstrus derartige Aussagen seien.

Trotz der außergewöhnlichen Situation haben wir in der Chefredaktion entschieden, das Interview zu veröffentlichen. Nicht ohne von Anfang an darauf hinzuweisen, dass wir uns von den Aussagen des Botschafters distanzieren. Es sei seine „abstruse Sicht des Krieges“, heißt es im Vorspann.

src: click

Eine Falter Journalistin kondensiert diese Position besser:

Die „Falter“-Journalistin Barbara Tóth hingegen vertrat die entgegengesetzte Auffassung. Sie meinte, die Fragen von profil transportierten ausreichend Kontext und zeigten das Maß an Desinformation auf. Das Interview sei ein „wichtiges Zeitdokument, weil es zeigt, wie russische Propaganda funktioniert“.

src: click

Öffentlich nimmt der Druck jedoch nicht ab, sondern zu - und so veröffentlich das Profil am 08.04. einen Faktencheck aufgrund von Bildern vom Explosionskrater vor der Geburtsklinik in Mariopol und drei Expertenmeinungen.

src: click

Die Chronologie lief also wie folgt.

Veröffentlichung > Kritik > Rechtfertigung man wollte der Öffentlichkeit zeigen wie russische Propaganda funktioniere > eigentlicher Faktencheck anhand eines Falls (Geburtsklinik von Mariupol), der im Interview nicht dezidiert genannt wurde - Faktencheck = drei Expertenmeinungen

Mich hat das damals fertig gemacht - da nichts davon mit journalistischen Arbeitsstandards kompatibel ist. Ich habe zwei Tage nach weiterem Material und dokumentierten Belegen gesucht - nichts.

In der Belingcat Datenbank zu Angriffen auf Spitäler und zivile Einrichtungen war der Angriff auf die Geburtsklinik nicht verzeichnet. UN Kriegsberichterstatter waren nicht vor Ort. (Gut, es war auch Mariupol im Krieg, nicht ganz so einfach.)

Zugegeben, der (von Spitälern auf die Geburtsklinik in Mariupol) Logiksprung ist nicht groß, und dass der russische Botschafter diesen Fall referenziert hat, ist durchaus wahrscheinlich, aber nicht gesichert.

Jetzt geht die Geschichte aber noch weiter -

Wenige Wochen nach dem Vorfall ist die Beauty-Bloggerin nun in einem Video aufgetaucht, in dem sie falsche Tatsachen über den Angriff auf die Klinik wiedergibt. Ein Twitter-Account, der mit der russischen Regierung in Verbindung steht, teilte ein Interview mit Wischegirskaja. Mitte März war sie von Russland noch beschuldigt worden, eine Krisendarstellerin zu sein.

Plötzlich leugnet Wischegirskaja die Ereignisse in Mariupol - in einem russischen Video

In dem neuen Video behauptet sie nun plötzlich, dass es im März gar nicht zu einem Bombenangriff auf die Klinik gekommen sei. Beobachter glauben deshalb, Wischegirskaja sei womöglich gegen ihren Willen auf russisch besetztes Gebiet nach Donezk gebracht worden. Das berichtet auch die ukrainische Zeitung „Obozrevatel“. Bestätigt werden konnte das allerdings nicht.

Geführt wurde das Interview von dem russischen Blogger Denis Seleznev, der das Video auch auf YouTube veröffentlichte und via Twitter und Telegram verbreitete. Russische Zeitungen greifen es ebenfalls auf und nutzen es zu Propagandazwecken. Auch auf Wischegirskajas eigenem Instagram-Account war es zu sehen.

In dem Interview wird sie gebeten, die Ereignisse im Krankenhaus am 9. März zu beschreiben. Daraufhin sagt sie, dass diejenigen, die nach dem Angriff im Keller des Krankenhauses zusammengekauert waren, geglaubt hätten, die Explosionen seien durch Beschuss und nicht durch einen Luftangriff verursacht worden, weil niemand Geräusche hörte, die auf einen Bombenabwurf hindeuteten.

Zahlreiche Hinweise deuten auf Luftangriff in Mariupol hin

Augenzeugenberichte und Videoaufnahmen von AP-Journalisten in Mariupol deuten jedoch auf einen Luftangriff hin, darunter das Geräusch eines Flugzeugs vor der Explosion, ein mindestens zwei Stockwerke tiefer Krater vor dem Krankenhaus und Interviews mit einem Polizisten und einem Soldaten am Tatort, die beide den Angriff als „Luftangriff“ bezeichneten.

src: click

Die BBC hatte etwas später die Gelegenheit die Bloggerin erneut zu interviewen:

On 9 March, she was chatting with other women on the ward when an explosion shook the hospital.

She pulled a blanket over her head. Then a second explosion hit.

“You could hear everything flying around, shrapnel and stuff,” she says. “The sound was ringing in my ears for a very long time.”

The women sheltered in the basement with other civilians. Marianna suffered a forehead cut and glass fragments lodged in her skin, but a doctor told her she didn’t need stitches.

[…]

“I was offended that the journalists who had posted my photos on social media had not interviewed other pregnant women who could confirm that this attack had really happened.”

She suggests this may help explain why some people “got the impression that it was all staged”. But by Marianna’s own account she was one of the last patients to be evacuated, and that was when the AP journalists arrived. The journalists interviewed other people at the scene. And they had nothing to do with the subsequent false story spread by Russian officials. We approached the AP for comment.

[…]

She filmed an interview with Denis Seleznev, a blogger who is a vocal supporter of Russian-backed separatists. There was speculation how free she was to say what she wanted.

Marianna says to me: “I had to describe the whole situation, as I saw it with my own eyes.”

My conversation with her was also arranged via Denis. Marianna speaks to me from his home. He is present throughout our chat but doesn’t interrupt. Marianna’s relatives and friends have assured me she is now safe.

[…]

Piecing together the truth

Much of what she says in her interview with me undermines the Russian government’s mistruths.

src: click

Halt nur nicht in den Punkten “niemand hatte geglaubt, dass die Explosionen durch einen Luftangriff verursacht worden sind [subjektive Wahrnehmung, zum Zeitpunkt des Geschehens, oder erzwungene PR]”, nicht in dem Punkt “Beobachter glauben deshalb, Wischegirskaja sei womöglich gegen ihren Willen auf russisch besetztes Gebiet nach Donezk gebracht worden” und nicht in dem Punkt “and then a second explosion hit”.

Zum “wurde sie zu Aussagen gezwungen Aspekt”, sie ist in ihre Heimatstadt im Donbas zurückgekehrt (click), diese ist immer noch durch russische Separatisten besetzt. Ihre Familie sagt der BBC es gehe ihr gut. Aber ein pro-separatist blogger sitzt im BBC interview immer noch neben ihr, der selbe der auch das Video aufgenommen hat in dem sie nicht mehr von einem Bombenangriff gesprochen hat.

Und dann gibt es das Videomaterial von den AP-Journalisten.

Gefilmt von Mstyslav Chernov (President of the Ukrainian Association of Professional Photographers (UAPF)) und Crew. (siehe: click)

Basierend auf vier sich selbst widersprechenden Interviews von Chernov (1,2,3,4) ergibt sich folgender Ablauf:

Chernov trifft eine Stunde vor Kriegsbeginn in Mariupol ein. Filmt in den ersten Tagen aus unerfindlichen Gründen bereits früh in Krankenhäusern. (Für einen AP Fotographen jetzt nicht unbedingt das Wunschmotiv schlecht hin. In späteren Interviews wird erwähnt, dass sie nur dort ihr Equipment laden konnten.)

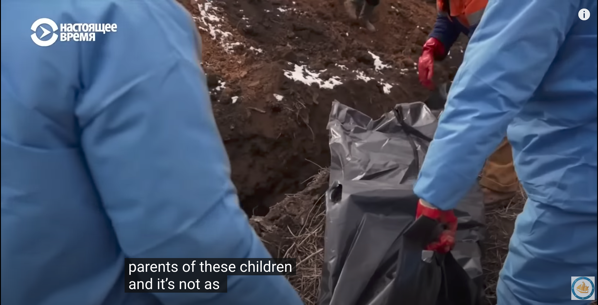

The deaths came fast. On February 27, we watched as a doctor tried to save a little girl hit by shrapnel. She died.

A second child died, then a third. Ambulances stopped picking up the wounded because people couldn’t call them without a signal, and they couldn’t navigate the bombed-out streets.

The doctors pleaded with us to film families bringing in their own dead and wounded, and let us use their dwindling generator power for our cameras. No one knows what’s going on in our city, they said.

Shelling hit the hospital and the houses around. It shattered the windows of our van, blew a hole into its side and punctured a tyre. Sometimes, we would run out to film a burning house and then run back amid the explosions.

src: click

Fährt am 09. März einfach in der Stadt rum, das Auto das sie nutzen wird immer wieder getroffen, zumindest ein Fenster zerstört, danach nutzen sies weiter. Bis es anschließend komplett verloren geht - dazu später mehr.

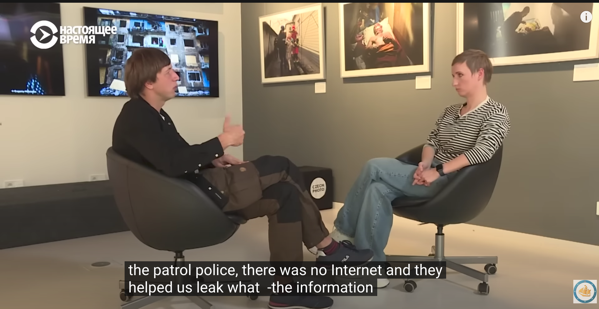

Sie fahren in der Stadt rum, sehen eine große Explosion und Rauch aufsteigen, und beschließen dort hinzufahren. Kommen bei der Geburtenklinik an und filmen. (siehe: click) Sie können nicht viel filmen, weil sie nur noch wenig Akku haben. Als sie mit dem Filmen fertig sind, sagt ihnen ein Polizist (den sie vor Ort treffen? (unklar)), der sie reden hört - “dieses Video-Material wird die Welt verändern” und hilft ihnen einen Platz zu finden von dem aus sie das Video hochladen, in drei Teilen über drei unterschiedliche Smartphones, und an dem sie ihr Equipment wieder aufladen können.

Our batteries were almost out of juice, and we had no connection to send the images. Curfew was minutes away. A police officer overheard us talking about how to get news of the hospital bombing out.

“This will change the course of the war,” he said. He took us to a power source and an internet connection.

src: click

Dann sind sie von dem Ort wieder weg, und hatten keine Internet Verbindung mehr.

In anderen Interviews hatten sie dann aber noch ein Sattelitentelefon und haben weitere Veröffentlichungen gepusht. (siehe: click) Kann Conjecture des Interviewers sein, unklar.

In the dark, we sent the images by lining up three mobile phones with the video file split into three parts to speed the process up. It took hours, well beyond curfew. The shelling continued, but the officers assigned to escort us through the city waited patiently.

Then our link to the world outside Mariupol was again severed.

Moment, sie haben das video also in drei Teile gesplittet über Mobiltelefone hochgeladen, nachdem ein Polizist, der sie zufällig vor dem Maternity ward reden hören hat ihnen gesagt hat “das wird die Welt verändern” und ihnen den Weg zu einem Ort gezeigt hat, an dems Internet gab und Strom um ihr Kamera Equipment wieder aufzuladen?

Ehm was für ein Internet denn?

src: click

Oh, aha. Moment, wieso splittest du das Video dann in drei Teile und lädst es von drei verschiedenen Smartphone hoch. Wer roamt denn da noch so im Satteliten Internet der Patrol Polizei, dass es Sinn macht drei Geräte gleichzeitig einzuloggen um mehr Priorität zu bekommen? Enorm böse, durchtriebene russische Hacker nehm ich an. Und oh, laut Video habt ihr das mehr als einmal benutzt um “Information zu leaken?”. Ja Mann du - der Polizei läuft man zufällig schon mal wieder über den Weg, das passiert schon mal.

We went back to an empty hotel basement with an aquarium now filled with dead goldfish. In our isolation, we knew nothing about a growing Russian disinformation campaign to discredit our work.

The Russian Embassy in London put out two tweets calling the AP photos fake and claiming a pregnant woman was an actress. The Russian ambassador held up copies of the photos at a UN Security Council meeting and repeated lies about the attack on the maternity hospital.

In the meantime, in Mariupol, we were inundated with people asking us for the latest news from the war.

So many people came to me and said, “Please film me so my family outside the city will know I’m alive.”

By this time, no Ukrainian radio or TV signal was working in Mariupol. The only radio you could catch broadcast twisted Russian lies — that Ukrainians were holding Mariupol hostage, shooting at buildings, developing chemical weapons. The propaganda was so strong that some people we talked to believed it despite the evidence of their own eyes.

The message was constantly repeated, in Soviet style: Mariupol is surrounded. Surrender your weapons.

On March 11, in a brief call without details, our editor asked if we could find the women who survived the maternity hospital [attack] to prove their existence. I realised the footage must have been powerful enough to provoke a response from the Russian government.

We found them at a hospital on the front line, some with babies and others in labour. We also learned that one woman had lost her baby and then her own life.

src: click

Am 11. März kontaktiert den Journalisten sein Editor und erklärt ihm, sie müssten mit den Frauen sprechen die sie aufgenommen haben [keine Bildrechte, nicht dokumentiert wer sie waren, …

“I was offended that the journalists who had posted my photos on social media had not interviewed other pregnant women who could confirm that this attack had really happened.”

src: click]

Chernov gibt in einem der Interviews an, als er diese Rückmeldung des Editors gehört hat, war ihm klar, das Material hat eingeschlagen - das war so emotional wirksam, dass Russland darauf reagiert haben muss.

On March 11, in a brief call without details, our editor asked if we could find the women who survived the maternity hospital [attack] to prove their existence. I realised the footage must have been powerful enough to provoke a response from the Russian government.

src: click

Dann gibt es eine Gedächtnislücke (eine in den Interviews nicht dokumentierte Zeitperiode) wie sie zu dem neuen Spital gekommen sind (“I’m looking for pregnant women, sure they are in a hospital near the front.”).

Sie kommen also am 11. März im Krankenhaus nahe der Front an, in das die schwangeren Frauen verlegt wurden. Finden heraus, dass eine der prominentesten schwangeren Frauen aus dem Video leider verstoben sei, Interviewen aber andere schwangere Frauen.

Jedoch auch nicht die Social-Media Influencerin, denn die gibt gibt noch am 17. Mai gegenüber der BBC an, man habe ja nur sie interviewt (vor Ort?) und ansonsten niemanden (siehe: click).

Diese Interviews mit anderen schwangeren Frauen werden nicht Teil des öffentlichen Newscycles, die sieht der Editor der Chernov desshalb anruft - aber nicht die Öffentlichkeit.

Als sie am 11. März in dem Krankenhaus ankommen - und nachdem sie die Interviews geführt haben, führt sie ein Militärangehöriger in den den siebenten Stock des Krankenhauses, erneut “da sie da Internet Verbindung hätten” (Ehm, kurzer sanity check - “As long as you have a clear line of sight from the satellites in space, the satellite signal strength being received will be exactly the same at head height that it will be on the top on a sky scraper. In this respect satellite dishes do not work like conventional TV aerials where height is usually very important to get a good signal.”, hurra, das Mobiltelefoninternet hat also wieder angefangen zu funktionieren! Im siebenten Stock! Oder hurra, jemand hat Skylink im siebenten Stock aufgesetzt, und kein Netzwerk Engineer war vorhanden, der das über mehr als ein Stockwerk extenden hätte können. In einem Krankenhaus.) und die Journalisten filmen dort den Hauptclip für das Promotion Material der späteren PBS Dokumentation 20 Tage in Mariupol, die später auf dem Sundance Filmfestival prämieren wird.

bei 2min in

(Yes, I’m with the journalist, yes I’m with the journalist, …)

In dem Video ist zu sehen, wie russische Einheiten auf das Gelände des Krankenhauses eindringen.

Der ukrainische Soldat im Video, der später von Chernov als “mehrere Soldaten im Krankenhaus” beschrieben wird, verschwindet direkt im Anschluss an das Video zusammen mit den anderen ukrainischen Soldaten aus dem Krankenhaus.

The Ukrainian soldiers who had been protecting the hospital had vanished.

src: click

Chernov und Crew bekommen eine Ärztekutte von den Ärzten im Krankenhaus und werden versteckt. Sie trauen sich zu diesem Zeitpunkt bereits nicht mehr aus dem Krankenhaus, da eine Schwester von einem russischen Scharfschützen vor dem Krankenhaus erschossen wurde:

The Ukrainian soldiers who had been protecting the hospital had vanished. And the path to our van, with our food, water and equipment, was covered by a Russian sniper who had already struck a medic venturing outside.

src: click

Jetzt stellt sich aber raus - mehr als naja.

src: click

Das ist ja beinahe wie verloren - da kann man ja schon mal verloren dazu sagen…

Hier ja auch: click

Sie verbringen die Nacht in dem Krankenhaus, schlafen in der Mitte auf den Gängen, damit sie nicht von Schrapnell getroffen werden.

Hours passed in darkness, as we listened to the explosions outside. That’s when the soldiers came to get us, shouting in Ukrainian.

It didn’t feel like a rescue. It felt like we were just being moved from one danger to another. By this time, nowhere in Mariupol was safe, and there was no relief. You could die at any moment.

We were the only international journalists left in the Ukrainian city, and we had been documenting its siege by Russian troops for more than two weeks. We were reporting inside the hospital when gunmen began stalking the corridors. Surgeons gave us white scrubs to wear as camouflage.

Suddenly at dawn, a dozen soldiers burst in, “Where are the journalists, for f***’s sake?”

I looked at their armbands, blue for Ukraine, and tried to calculate the odds that they were Russians in disguise. I stepped forward to identify myself. “We’re here to get you out,” they said.

The walls of the surgery shook from artillery and machine-gun fire outside, and it seemed safer to stay inside. But the Ukrainian soldiers were under orders to take us with them.

src: click

Am Morgen kehren ein dutzend Soldaten zum Krankenhaus zurück, alle mit dem Befehl sie da rauszuholen.

Moment, sagte das Al Jazeera Interview noch Soldaten zu ihnen? In dem Interview hier wars eine Polizei task force:

src: click

Naja, ist ja quasi das selbe… Am Anfang des Tages im siebenten Stock des Krankenhauses waren es aber definitiv Soldaten, das sehen wir im Video.

Sie fassen sich ein Herz, geben sich zu erkennen und werden auf Befehl aus dem Krankenhaus evakuiert.

Dann gibt es wieder eine Gedächtnislücke - denn es ist unklar wohin, in jedem Fall in einen dunklen Keller.

We reached an entryway, and armoured cars whisked us to a darkened basement.

src: click

Oder ins Stadtzentrum, ich mein das ist ja auch schwer zu differenzieren:

src: click

src: click

Dann verschwinden die 12 Militärs erst mal wieder aus der Erzählung und im Stadtzentrum, Verzeihung, Keller treffen sie dann nur einen Polizei-Officer, der ihnen folgendes erzählt:

We reached an entryway, and armoured cars whisked us to a darkened basement. Only then did we learn from a policeman why the Ukrainians had risked the lives of soldiers to extract us from the hospital.

“If they catch you, they will get you on camera and they will make you say that everything you filmed is a lie,” he said. “All your efforts and everything you have done in Mariupol will be in vain.”

The officer, who had once begged us to show the world his dying city, now pleaded with us to go. He nudged us toward the thousands of battered cars preparing to leave Mariupol.

src: click

Das Militär das mittlerweile wieder zu einem Polizisten geworden ist, den sie aber bereits länger kannten (?) -

The officer, who had once begged us to show the world his dying city, now pleaded with us to go. He nudged us toward the thousands of battered cars preparing to leave Mariupol.

src: click

- der erkennt wie wichtig ihr Videomaterial für die Welt ist (drei Tage nachdem ihr Videomaterial von der russischen Botschaft kommentiert wurde und für ein Medienspektakel gesorgt hat - und nachdem der russische Vertreter es in einem UN security council meeting diskreditiert hatte), und lässt sie also einfach gehen.

Das Videomaterial wird nicht kopiert, wird ihnen nicht abgenommen, sie sind einfach von 12 Militärs unter Einsatz ihres Lebens von einem Krankenhaus, in einen Keller gerettet worden, wo aus den Militärs wieder ein Polizist wurde, den sie aber bereits kannten (?), der ihnen gesagt hat, wie wichtig ihr Material ist, und sie dann gehen lässt.

Dann nehmen sie das Material, setzen sich (drei Tage später) - mit dem Material in einen Hyundai von ner wahllosen “Familie von drei Leuten” - riskieren mit dem Material und ihrer Präsenz deren Leben (“We were lucky, that they didnt see our faces.”), fahren durch 15 russische Checkpoints und sind dann draußen.

I felt amazingly grateful to the soldiers, but also numb. And ashamed that I was leaving.

We crammed into a Hyundai with a family of three and pulled into a five-kilometre-long (3.1-mile-long) traffic jam out of the city. Approximately 30,000 people made it out of Mariupol that day — so many that Russian soldiers had no time to look closely into cars with windows covered with flapping bits of plastic.

People were nervous. They were fighting, screaming at each other. Every minute there was an aeroplane or [air raid]. The ground shook.

We crossed 15 Russian checkpoints. At each, the mother sitting in the front of our car would pray furiously, loud enough for us to hear.

As we drove through them — the third, the 10th, the 15th, all manned with soldiers with heavy weapons — my hopes that Mariupol was going to survive were fading. I understood that just to reach the city, the Ukrainian army would have to break through so much ground. And it wasn’t going to happen.

At sunset, we came to a bridge destroyed by the Ukrainians to stop the Russian advance. A Red Cross convoy of about 20 cars was stuck there already. We all turned off the road together into fields and back lanes.

The guards at checkpoint 15 spoke Russian in the rough accent of the Caucasus. They ordered the whole convoy to cut the headlights to conceal the arms and equipment parked on the roadside. I could barely make out the white Z painted on the vehicles.

As we pulled up to the 16th checkpoint, we heard voices. Ukrainian voices. I felt an overwhelming relief. The mother in the front of the car burst into tears. We were out.

We were the last journalists in Mariupol. Now, there are none.

src: click

Und die Erzählung endet mit dem Zitat das ihnen der Polizist im dunklen Keller vermittelt hat “ihr wart die letzten Journalisten in Mariupol”.

Mittlerweile wissen wir dass sie 30 Stunden Material hatten. 30 Stunden 1080p@60 bei 8Mbps compressed (Youtube Qualität) ergibt 200GB. In Bluray Qualität compressed (40Mbps) 1TB. Und in Apple Prores 6TB. Die Hälfte, wenn sie nicht in 60Hz aufnehmen. Das sind keine riesigen Datenmengen. Gesetz dem Fall der Polizist in dem “dunklen Keller”, den die Journalisten bereits kannten (?, unklar) war Militärpolizei - und weiß bereits, dass Chernov später einen PBS Deal für eine Dokumentation bekommt in dem das Material verwertet wird, die beim Sundance Filmfestival prämiert werden wird - mach ich da doch Backups. Und schick die unabhängig von den Journalisten aus dem Land.

Ich lass die Journalisten nach einer Rettungsaktion mit 12 Mann doch nicht einfach in nen Keller kommen und entlasse sie dann wieder, damit sie sich bitte einen privaten Fluchtweg suchen, und mit dem Material das sie transportieren (das aber bereits um UN securiy council zum Gegenstand von Statements geworden ist) eine Familie mit drei Personen gefährden - die tot wäre, wenn die Journalisten in einem von 15 Checkpoints identifiziert werden. Und all das (bereits im UN security council referenzierte) Material weg.

Der Upload von 200GB mittels Starlink dauert bei 40Mbps zwei Tage, sieben Stunden. Von 100GB einen Tag. Und 40Mbps Upload sind kommerziell erwerbbar, da geht sicher noch mehr.

Gesetz dem Fall der Polizist ist nur “ein zufälliger Polizist in einem dunklen Keller” - warum hat ein Militär Aufgebot von 12 Mann mit Befehl die Journalisten zu evakuieren, die Journalisten zu dem gebracht?

Überraschung - am 26. Jänner dieses Jahres stellt sich heraus im ersten Interview vom 21. März des Vorjahres, dem schriftlichen, dem das über 20 journalistische Outlets aufgegriffen haben - ein wesentliches Detail fehlt:

But yes, the policeman that was with us, that helped us in the last days [Evakuierung durch das Militär am 12.03., Verlassen von Mariupol am 15.03.], he also risked his life and you know, safety for - of his family, he took us in his car, and as the first humanitarian corridor was open, they tried to take us out from the city, and that worked, because fist days were very chaotic, so we’re going through 15 checkpoints, you know, cameras and hard drives hidden, flak jackets hidden, we should have them in the city though, but ok I’m glad that we took them anyway and the car is full of bags and russians are checking our documents and this family… Every checkpoint we arrive uh, Vladimir’s wife just praying, I can hear her praying. We crossed all these checkpoints and at night, we dont see where we are driving, but we arrive at the next checkpoint, and instead of russian we hear Ukrainian language, and she bursts into tears at that moment. Again, I should have filmed it - but yeah…

src: click

Never mind that you should have filmed the persons wife who saved you breaking out into tears, as the flipping journalist that you are, only shooting news material --

das ESSENTIELLE DETAIL das in dem schriftlichen Interview das an 20 Medienoutlets ging (Aljazeera) gefehlt hat war FUCKING Vladimir, sein Police handler in den letzten Tagen, die Person zu der ihn mir hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit das 12 köpfige Team an Soldaten gebracht hat, nachdem sie Chernov und seine Crew aus dem Krankenhaus an der Front evakuiert haben (mit dem Auftrag sie zu evakuieren) der selbe Vladimir - der dem Journalisten laut Aljazeera interview zuvor bereits einmal gesagt hat - “zeigt der Welt meine sterbende Stadt”.

Hat Vladimir die 12 köpfige Einsatztruppe in das Spital geschickt?

Naja - wer kann das schon so genau sagen… Chernov nicht:

src: click , well - they already were going through the battlefield and took us out. Ist wie dieser Satz endet. Im Aljazeera Interview hatten sie (die Soldaten übrigens) dezidiert den Befehl die Journalisten zu befreien. Wir erinnern uns:

Suddenly at dawn, a dozen soldiers burst in, “Where are the journalists, for f***’s sake?”

src: click

Naja, so ein kleines Detail, wer kann da schon böse werden…

The officer, who had once begged us to show the world his dying city, now pleaded with us to go. He nudged us toward the thousands of battered cars preparing to leave Mariupol.

src: click

Wobei ONCE wohl definitiv nicht im Zeitraum nach der militärischen rescue operation war, sondern irgendwann mal davor.

Und sie bereits am Tag der Bombadierung des Maternity Wards eine “Polizeieskorte” gehabt haben, die ihnen den Weg zu einem Ort gezeigt hat an dem sie ihre Kameras laden und das Video senden konnten.

Diese Eskorte war dann am nächsten Tag aber plötzlich wieder weg. So ein Pech aber auch.

In the dark, we sent the images by lining up three mobile phones with the video file split into three parts to speed the process up. It took hours, well beyond curfew. The shelling continued, but the officers assigned to escort us through the city waited patiently.

Then our link to the world outside Mariupol was again severed.

We went back to an empty hotel basement with an aquarium now filled with dead goldfish. In our isolation, we knew nothing about a growing Russian disinformation campaign to discredit our work.

src: click

Naja, gut, dass sie sie in den letzten drei Tagen wieder hatten, denn -

src: click to one of the police headquaters, für die die sich fragen wie der Satz weiter geht.

src: click to one of the police headquaters, für die die sich fragen wie der Satz weiter geht.

Und zwei Tage später stehen sie im siebenten Stock des Krankenhauses an der Front, filmen den Militärschutz dort, während der an seine Basis funkt “I’m with the journalist, yes - the journalist”.

Naja - dieses Detail der Erzählung wurde im ersten Interview (dem schriftlichen, das über 20 Kanäle ging), eben zu “wir haben uns dann mit einer Familie in einen Hyundai gesetzt um aus der Stadt zu kommen.”

IN EINEN HYUNDAI?! Danke für dieses wesentliche Detail!

Es kommt jetzt aber noch mehr, jetzt existiert auch dieses vierte Interview -

Transkript:

I: Hi there. It’s Sharon Waxman, the editor of the Wrap coming to you from the Wraps 2023 studio at the Sundance Film Festival with NFP. Thank you so much to the cast, to the people who created the film, 20 days in Mariupol, a very moving and tough documentary about the war in Ukraine. So I’m letting everybody introduce themselves, starting with the Director. Yeah. Because you think I’m gonna get your name, right? Probably not.

C: My name is Mstyslav Chernov. I’m director and cameraman for this film.

I: Welcome, welcome. That. No, you get your own [microphone].

MM: I’m Michelle Meisner. I’m the producer and editor of the film.

EM: Hi, I’m Evgeniy Maloletka. I’m a photographer.

S: And I’m Vasilisa Stepanenko, I’m field producer.

I: Ok, great. So this is a very difficult picture of a very difficult war that is still going on and in where people are dying every day, tell us why you chose to sort of take this slice, this moment in time, which goes back to the beginning of the war, and tell the story - because the story’s not done, it’s still ongoing.

C: I think Mariupol is a city as a - one of the events that happened in the beginning of the full scale Russia’s invasion in Ukraine is extremely symbolic for Ukrainians, and historically symbolic because being being a strategically important city for Russia to try to take from Ukraine, it’s also had so much tragedy packed in there in this short period of time. Over three months and being able to show this tragedy to the world means a lot to us, but also we feel, and we found out only later when we left Mariupol. When we broke out of the siege, only then we found out how much what we did there and what happened there changed the world’s perspective on the invasion. So it’s also symbolic from that side. But throughout the coverage, throughout this 20 days of the film is called 20 days in Mariupol - throughout that 20 days, we’ve been sending news dispatches or quite short packages of videos, one minutes, 2 minutes.

I: Sending them to - putting them on YouTube - where do you see them?

C: So associated - we work for AP.

I: All of you guys work AP? Not producer obviously.

C: Yeah, we are, we are AP team and Michelle is with Frontline - so when we left Mariupol we took out safely around 30 hours up to 30 hours of footage and most of it wasn’t published. And I felt that we need to do more about Mariupol. We felt quite guilty that we left and Mariupol was still under the siege. People were still dying every day. And I felt that we needed to do more. So, collaboration with Frontline started [passive] and we assembled the film out of those hours.

I: So just to be clear, you were actually working journalists for the Associated Press, yes, but you had all this extra material that you wanted, that you felt like you hadn’t totally told the story, even though you’re sending dispatches out to the world every day - basically..

C: Right. So in the beginning it wasn’t when it was shot, it wasn’t even intended to be a documentary. This was intended to be a news dispatch, daily news dispatches and they were shot this way. So that’s partially was a challenge when we left with all this footage was to to connect them to - into a narrative, which -

I: So were you all there as a team?

MM: Yes

I: These three, what was your role?

MM: Yeah, so these journalists were on the ground in Ukraine, where they are all from to cover the invasion and they had a sense that the city of Mariupol would be one of the main targets. And so they went there, to cover for the AP and the city gives you see in the film, the city is surrounded and it becomes impossible for anyone to leave, including them, and they continued filming. Infrastructure is attacked, civilian infrastructure. The things they witnessed, you might remember the maternity bombing, the maternity ward, that ward that was bombed, they were there. They were the ones who were on the ground filming it. So they’re very humble and well, not like admit that the reason why we have documented evidence of these potential war crimes is because they were on the ground filming it. As he said, the Internet became very sporadic. And so they had to find places where they could upload the stories and send them out to the world. They were only able to get some out, but really important footage that everyone saw. And then when they left, he had 30 hours of footage that told a real story about the 20 days that they were there. So, -

I: So where did you?

MM: So I came in as an editor, so I work for Frontline PBS and we started working with Mstyslav, who actually had a pretty clear vision for how the story could come together. And we assembled a film and we didn’t know if it would be a short at first and then we realized that it actually did - it could really fill a 90 minute feature. And so we put that together and it shows both how it - I think that what was like interesting about collaborating as somebody who wasn’t on the ground with them and why it’s important sometimes to work in a team where you aren’t - uh, I was looking at the footage in a in a way that I could see Mstyslav - like personality shine through in the way that he was filming things. The way that a tragedy would happen and he would drop the camera and it would still be, you could just, like, feel the emotion coming from him and get to know him in that way. So he became sort of like a the the perspective through which you’re seeing this unfold. You see Evgeniy and Vasilisa, you know, working alongside each other, really harrowing events, hard conditions and so we’re able to show that in the -

I: I wanted to ask about this because this is something that we’ve only just started I think scratching the surface about what is the impact due to the bearing of witness and your job is to go out and watch people suffer. You know, and document it. And I understand that the human impulse to feel the need to document it so that - for all sorts of reasons, so that the world will see it and they will stop it - which they haven’t, or history will have that for all time to be able to refer to it, so it’s a responsibility, but there’s a there’s clearly a very serious toll on the people who put themselves - and also all the medical workers and all the, you know, all the people, not to mention the people who are actually going through it, just watching a little girl staring into your camera and crying! It’s. Unbearable like that. She didn’t even die! You know, she’s not even wounded, she’s just so torn up and she’s she’s 5 - she’s 6 - it’s, it’s almost, you know, it’s hard to watch, so I can only imagine what it’s like - I can’t imagine what it’s like is what I’m saying - to live through. So I wanted to ask you, all of you guys who did that, like what, what was the toll, what, what was the impact on each of you to? Let’s start in the back and then, Mstyslav, you can…

S: It’s hard to imagine here that we saw - like I remember my feelings that when we were here, and when we watch all the scenes, how when we watch how the children died. The only chance that we had is to show the whole world, to let them understand what’s going on, how it can be going on in our time, in 21 century. So it was only one month old, that’s why. Yes, personally I felt big pain, like Ukrainian, like a human, like everyone in this world. But I understood that it’s really important that every one of us understood it. So that’s why we did it. And now that this film could watch everyone. It’s really, really important.

EM: They’ll use it. My hometown is - the name of the city is Berdjansk. It’s next on the west from Mariupol and actually it’s mostly you know my homeland where I grew up and the people who filmed, photographed and in these such conditions in this pain not like we just, some actors just you understood on the ground, that this were real souls - who are passed away. You know, and these kids who just you know how their parents bring them already dead to the hospital and doctors try to resuscitate them or do their animation processes. You document this and - with the tears in their eyes. You know, like you continue to do this, and the doctor is screaming “Show this to Putin” - because, because they might get to see this. Are they killing Ukrainians? That time, and this is, really hard to understand for ourselves as well - that this is. You know. Our relatives, our friends, it’s happened with all of us, all around Ukraine, all around the contact line and what we witnessed it in just one short period of time. Ohh. And that’s it. But it’s happened all around the area or like where Russia invaded.

C: It’s been almost a year and the film is called 20 days. So you look at this 20 days and you know what’s - what happened after every day in Ukraine. That is - nothing changed. It was happening every day what you see, but also we felt obligation as journalists, but as well as Ukrainians, this is our community, this is our country, and we do feel an obligation to keep telling these stories to to make sure that, everything that was that possible to document, will stay in history, so maybe in the 50 years of time or 100 years of time, someone who would ask what happened - so you know how that invasion started, what happened to Mariupol? Will go and see this, and will know how terrible the war is. How imparable human pain is and from this perspective, although the film is told from the perspective of a journalist - it’s still really about people. And about Mariupols residents and I think our feelings, these feelings of journalists or documentary makers right now is - it’s quite secondary it’s very important here for it not to stand on the way to - for the audience to feel what actually residents of Mariupol felt.

I: Thank you. Well, the film is very intense and sometimes difficult to watch, but it’s important for that reason. So thank you for bringing your film to Sundance, 20 days in Mariupol. It’s going to be out on Frontline and PBS.

MM: Eventually, yes. Yeah. Well, later this year, I presume. Yeah, yeah. We’ll see what life it takes over the next few months, and later this year we’ll be airing on PBS.

I: Thank you for the film and thanks for coming to our studio.

und damit kommen noch zwei weitere Widersprüchlickeiten mit dazu -

Over three months and being able to show this tragedy to the world means a lot to us, but also we feel, and we found out only later when we left Mariupol, when we broke out of the siege, only then we found out how much what we did there and what happened there changed the world’s perspective on the invasion.

- die Journalisten hätten erst als sie aus Mariupol weg waren erkannt, dass das Material das sie hatten wichtig war, denn sie hatten dann erst gesehen, dass das was in Mariupol geschehen ist, die Perspektive der Welt verändert hat.

The Russian Embassy in London put out two tweets calling the AP photos fake and claiming a pregnant woman was an actress. The Russian ambassador held up copies of the photos at a UN Security Council meeting and repeated lies about the attack on the maternity hospital.

In the meantime, in Mariupol, we were inundated with people asking us for the latest news from the war.

So many people came to me and said, “Please film me so my family outside the city will know I’m alive.”

src: click (Inhaltlicher Widerspruch? Das hier zitierte “in the meantime” Bezieht sich auf die Zeit zwischen dem 09.03. und dem 11.03.. Hier erklärt Chernov, dass er sich über den aktuellen Verlauf des Newscycles von seinem Editor auf dem Laufenden halten hat lassen.)

Im Aljazeera Interview war das [das Material das so wichtig war] noch der Grund, warum der Polizist Vladimir (*hust*) ein 12 köpfiges Militärteam zu ihrer Rettung in ein Spital in der nähe der Front gesendet hatte, mit dem Befehl die Journalisten zu evakuieren (unklar ob der von ihm kam):

“If they catch you, they will get you on camera and they will make you say that everything you filmed is a lie,” he said. “All your efforts and everything you have done in Mariupol will be in vain.”

The officer, who had once begged us to show the world his dying city, now pleaded with us to go. He nudged us toward the thousands of battered cars preparing to leave Mariupol.

src: click

HE NUDGED YOU TOWARDS THE THOUSANDS OF BATTERED CARS PREPARING TO LEAVE MARIUPOL? VLADIMIR DID? THE GUY WHO YOU ACTUALLY DROVE WITH, IN HIS CAR, TO GET OUT OF MARIUPOL?

Amazing.

It was a Hyundai, right? Better state that it was a Hyundai, in the first interview in March of 2022, and leave the little fact, that it was Vladimir, the police handlers Hyudnai for January 2023. For an interview at the Sundance film festival press circuit.

Die Kontaktanbahnung mit PBS verlief dann übrigens passiv:

C: And I felt that we needed to do more. So, collaboration with Frontline started and we assembled the film out of those hours.

Die PBS Producer und Editorin hatte sich noch überlegt ob sie aus dem Material eine narrative Geschichte bauen kann, aber Chernov hatte bereits eine eigene Geschichte die er erzählen wollte -

MM: So I came in as an editor, so I work for Frontline PBS and we started working with Mstyslav, who actually had a pretty clear vision for how the story could come together.

Aus den beiden Polizisten die dem Team gesagt haben “zeigt das der Welt!” (der eine der sie vor der Geburtsklinik hat reden hören, und sie zu einem Ort mit Internet und Strom zum Laden ihres Equipments gebracht hat, und der andere in dem dunklen Keller) - ist mittlerweile ein Arzt geworden:

You know, and these kids who just you know how their parents bring them already dead to the hospital and doctors try to resuscitate them or do their animation processes. You document this and - with the tears in their eyes. You know, like you continue to do this, and the doctor is screaming “Show this to Putin” - because, because they might get to see this.

(Bei einem zweiten media appointment ebenfalls.)

Und jetzt haben wir endlich eine Premiere beim Sundance Filmfestival!

Jetzt gibt es im vierten Interview aber noch einen Punkt der dezidiert prüfbar ist:

C: So in the beginning it wasn’t when it was shot, it wasn’t even intended to be a documentary. This was intended to be a news dispatch, daily news dispatches and they were shot this way. So that’s partially was a challenge when we left with all this footage was to to connect them to - into a narrative, which -

Die Videosnippets sein geschossen worden “wie für einen “news dispatch” - ohne emotionales Narrativ, ohne ein Leiten des Gedankengangs des Zuschauers durch Kameraschwenks, …

Eben wie für einen Newscast.

Nun, ehm - nein.

Bildbeispiele:

Es gibt eine Einstellung in der Krankenhausmitarbeiter rauchen, dann Fokus auf die Gesichter, “defiance” als Emotion, dann sofort ein Schwenk auf eine ukrainische Flagge über ihnen.

Es gibt die Einstellung im siebenten Stock des Krankenhauses an der Front, in dem die Hauptkamera die Reaktion des Soldaten filmt, der Kameramann dem Soldaten in einen zweiten Raum nachrennt, um seine Reaktion festzuhalten, während eine simple Kamera mit Teleobjektiv, die pickupshots der sich draußen zusammenziehenden Panzer macht. Der Soldat fordert den Journalisten dann auf das zu zeigen (Film it!), der rennt zurück in den anderen Raum beginnt erstmalig durchs Fenster die eigentlichen Geschehnisse zu filmen, und in dem Moment schneidet die Editorin des Film zu Aufnahmen aus dem Teleobjektiv der anderen Kamera um - die Pickup shots macht.

Es gibt mehrere Einstellungen bei denen der Ausgangspunkt einfach head and shoulder close-ups sind die dann zum close up reingehen:

Es gibt mehrfach Einstellungen aus der Verfolgerperspektive (Kameraman läuft mit):

Selbe Perspektive mit Voice over: “Mass graves where children were buried.”

Superclosups von zitternden Händen:

Froschperspektive mit Zoom auf Hände durch die Erde riselt:

Nicht EINE dieser Einstellungen eignet sich für ein Newscast Format. JEDE dieser Einstellungen verwendet “subjektive Kamera” als Erzähltechnik.

Dass das Material sein soll, das eigentlich für einen Newscast gedreht wurde, aber welches man später nicht verwendet hat - und bei dem man dann erst nach der Flucht aus Mariupol erkannt habe, dass man damit doch eine narrative Erzählung schneiden kann, die einen 90 minütigen Kinofilm trägt, ist eine simple Lüge.

Keine andere Interpretation möglich.

Auf der anderen Seite ist das aber auch das beste Beispiel das sich Profil denken konnte, um der österreichischen Bevölkerung zu verdeutlichen was russische Propaganda ist.

Worauf die gesamte Medienlandschaft Österreichs die russische Seite von der Berichterstattung ausgeschlossen hat.

Kauf auch du morgen dein Kino Ticket zur Wahrheit.

Zusatz:

Dieses Video bei 8:30 in ist auch nicht schlecht:

Es spricht Evgeniy Maloletka, Fotograf der Chernov Crew, diese hörte Explosionen in der Nähe der Asowschen Universität und anderswo - es gab dort eine Reihe an Explosionen und eine davon war in einem Krankenhaus direkt gegenüber. Also beschlossen sie dort hinzufahren. (Keine Erwähnung des Rauchs mehr, der sie dort hin gelockt hat. Wie im ersten schriftlichen Interview das an 20 News outlets ging. (Aljazeera Interview)) Interviewerin fragt nach - hätte es sein können, das das Krankenhaus für militärische Zwecke genutzt wurde? Antwort: Versuchen wirs zu objektivieren, eine Militärinstallation hat Schützengräben, Stellungen, militärische Ausrüstung - in dem Moment in dem wir da waren, haben wir nichts davon gesehen. Wir wissen, dass es dort ein Krankenhaus gab in dem verwundetes ukrainisches Militärpersonal behandelt wurde, aber es ist nicht direkt im Maternity Ward zu dem wir gefahren sind, es ist ein anderes Gebäude, und das wurde am Ende nicht getroffen.

Das ISW hat da praktischer Weise eine Karte:

hat aber leider, was will man machen, vergessen Asowsche Universität auszuschreiben.

edit: Wer am Ende noch ein Interview sehen möchte, das das alles ausspart: